Biden’s student-debt pledge stalls, frustrating supporters

Americans owe around $1.6 trillion in federal student loans and more than $130 billion in private student loans

Chief economist slams Biden's ideas to put student loans on hold

Brian Wesbury explains the potential consequences of the president's idea, and discusses how the administration is giving people incentives not to work on 'Making Money'

Joe Biden said during his presidential campaign that he would reduce student debt for millions of Americans, but his allies remain divided on the issue, and some of his supporters are losing hope he will deliver.

Melanie Kelley, 38 years old, of Denver, has $125,000 in student loans. When the Biden administration’s pandemic-related pause on student-loan payments ends in May, she will owe $1,000 a month.

"It’s become this unmanageable beast for me," she said. "May isn’t that far away. How am I going to figure this out?" A management consultant, she said she has worked as a DoorDash driver to supplement her income, but her debt has kept her from starting a family or buying a house.

BIDEN HAS CANCELLED $5B IN STUDENT LOANS UNDER THIS FORGIVENESS PROGRAM: DO YOU QUALIFY?

"A lot of people are not going to vote again because they feel like they’re not being heard," said Ms. Kelley, who voted for Mr. Biden in 2020.

Ms. Kelley is one of around 43 million Americans with student debt. As a candidate, Mr. Biden endorsed canceling $10,000 in student debt per borrower through legislation and proposed forgiving tuition-related federal debt for people who earned undergraduate degrees at public colleges and universities, as well as schools that historically serve Black and minority students.

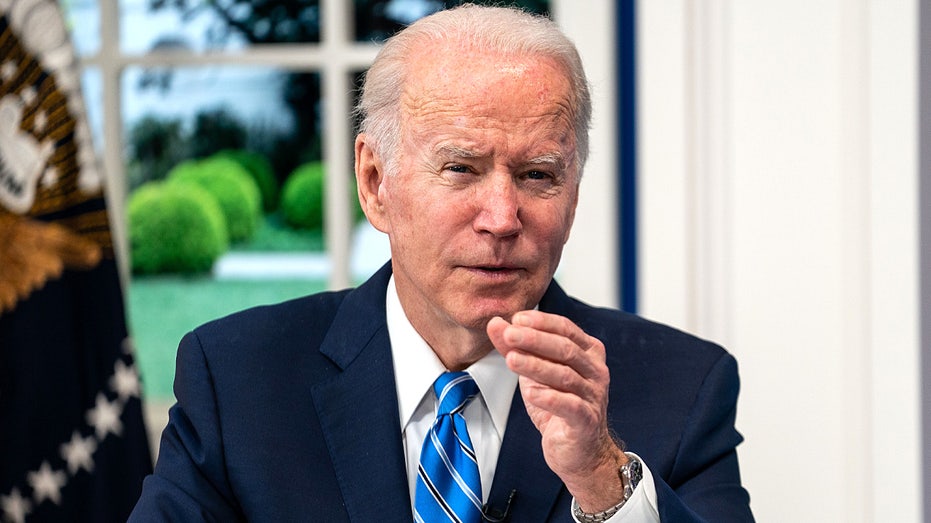

WASHINGTON, DC - DECEMBER 27: President Joe Biden and the White House COVID-19 Response Team participate in a virtual call with the National Governors Association from the South Court Auditorium of the Eisenhower Executive Office Building of the Whit (Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images / Getty Images)

All told, Americans owe around $1.6 trillion in federal student loans and more than $130 billion in private student loans, according to the data firm MeasureOne.

Legislative efforts to forgive student debt have sputtered in Congress, and progressive lawmakers are ratcheting up pressure on Mr. Biden to take executive action, calling on him to cancel up to $50,000 in debt per borrower.

"He must do this," Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D., Mass.) said. "It’s the right thing for generational equality; it’s the right thing for racial equality; and it’s the right thing for strengthening our economic future."

$5.8B IN STUDENT LOAN DEBT CANCELLED THROUGH TOTAL AND PERMANENT DISABILITY DISCHARGE

Many Republicans oppose debt cancellation. House Republican lawmakers argued in a letter last year that doing so would be "an affront to the millions of borrowers who responsibly repaid their loan balances."

Lew Gardner, 58, of Las Vegas, joined the Army nearly 38 years ago in part because of the promise that the government would help him repay his student loans. But he also took out private loans that weren’t eligible, and his balance peaked around $45,000 before he finished paying them off in 2005. He bristles at suggestions from elected officials that taxpayer money should be spent to forgive debt.

"What looks good is ‘Let’s just wipe the debt clean and then you’ll vote for me again,’" said Mr. Gardner, who supported Donald Trump in the 2020 election. "That’s really unfair for the taxpayers."

Since taking office, Mr. Biden has extended a pandemic-related pause on student-loan payments initiated under the Trump administration and overhauled student-debt forgiveness programs for people with disabilities and people who work in public service jobs, discharging the debt of roughly 675,000 borrowers, according to the Education Department.

Mr. Biden has revealed little publicly about whether he plans to take additional action to forgive student debt.

During a nearly two-hour news conference last month, the president avoided answering a question when asked about his campaign promises on the subject. White House officials said he continues to support legislation to eliminate $10,000 in student debt per borrower, despite its lack of a path forward in Congress. The officials said the administration is weighing additional executive branch actions to relieve debt, but declined to detail them or provide a timeline for their rollout.

CAN AN INCOME-CONTINGENT REPAYMENT (ICR) PLAN HELP GET MY STUDENT LOANS FORGIVEN?

The debate over whether Mr. Biden can wipe away billions in federal student debt with the stroke of his pen has divided some of his allies, according to people familiar with the discussions. Some have argued that such a move would energize young voters. Others have urged caution and encouraged him to defer to Congress, while raising concerns about whether the administration has the legal authority to act on its own.

Mr. Biden has expressed skepticism about universal debt forgiveness, arguing against canceling debt for people who attend elite private universities. He has said he opposes forgiving up to $50,000 in student debt for all borrowers and has suggested his executive authority is limited.

A January poll found that 49% of the public—including 70% of Democrats, 44% of independents, and 25% of Republicans—supports forgiving student- loan debt from public colleges and universities. Thirty-five percent of respondents said they were opposed, and 17% said they were not sure.

Biden supporters with student debt said in interviews that they are growing impatient. Though they praised Mr. Biden’s temporary extension of the pause on student-loan payments, many said they are left worrying about what will happen when that program lapses.

"I have no faith in Biden at all on this issue," said Ryan Velez, 36, of Louisville, Ky., who voted for Mr. Biden in 2020. Mr. Velez said he has more than $150,000 in student debt, a burden that has affected every part of his life—from his relationships to his job prospects.

Mr. Velez criticized Mr. Biden for supporting a sweeping 2005 bankruptcy overhaul that, except in rare circumstances, prohibits discharging private student loans through bankruptcy. "Taking away bankruptcy protections has obliterated any person’s hope who gets in this debt trap of getting out," Mr. Velez said.

WHAT TO DO IF YOUR STUDENT LOAN SERVICER IS SHUTTING DOWN

During his presidential campaign, Mr. Biden distanced himself from the bill, contending that he had backed it because it was going to pass anyway and worked to improve it. He proposed ending the bankruptcy restrictions, but Congress hasn’t acted on the issue.

Illustration by Ian Jopson, shared from Fox News CMS. (AP Newsroom / AP Newsroom)

Starting in 1990, Congress began to incorporate expected future loan repayments into its budgeting for student-loan programs. Loans became a potential source of profits, by assuming that most borrowers would repay with interest. This created an incentive for Congress to expand student lending. Doing so would increase access to higher education either at no cost to the government or with a gain in federal revenue—at least on paper.

Borrowing surged, but repayment rates have plummeted, especially in recent years. When repayments come in lower than expected, the Treasury Department fills the gap with cash infusions to the Education Department. In fiscal year 2019, before the pandemic pause on repayments, the Federal Student Aid office of the Education Department projected the need for a $124.5 billion infusion.

Legal scholars and advocates differ on whether the administration could pursue broad student-debt cancellation without congressional action. The debate centers on how courts would interpret the Education Secretary’s powers under the 1965 Higher Education Act, which allows the secretary to "consent to modification" of loans, and "compromise, waive, or release" unspecified amounts of student debt.

Advocates for broad cancellation say the lack of explicit constraints in the law is deliberate, giving the executive branch flexibility to manage its relationship with borrowers. They note that past presidents of both parties have used the law to forgive debt on a more limited scale. "The power is there," Ms. Warren said. "We just need the president to step up and use it."

HERE'S WHO HAS QUALIFIED FOR STUDENT LOAN FORGIVENESS UNDER BIDEN

The Trump administration argued that the law doesn’t give the Education Department carte blanche to do what it wants with the debt portfolio, sticking to the doctrine that Congress doesn’t "hide elephants in mouseholes," in the words of the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia.

"Courts should not be in the position of reading into statutes powers that Congress did not explicitly provide to agencies," said Reed Rubinstein, who served as acting general counsel for the Education Department under Mr. Trump and advised former Secretary Betsy DeVos against blanket debt forgiveness.

The law’s ambiguity may be one reason why the administration has yet to act. A series of redacted emails and memos was released by the Education Department in August showing that the administration was wrestling with the legal question.

Biden administration officials have said the administration is preparing a legal memo detailing the executive branch’s authority to eliminate student debt. But the administration hasn’t disclosed what the memo says, prompting more than 80 Democratic lawmakers, including Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D., N.Y.), to press Mr. Biden to release the document publicly.

Studies show that forgiving student debt could help Black borrowers, who are more likely to face long-term financial burdens from student loans. But a Brookings Institution study released last month argued that across-the-board student debt relief is regressive, calling the policy a "costly and ineffective way to reduce economic gaps by race or socioeconomic status" because student debt is concentrated among higher-wealth households. The study instead calls for more targeted, means-tested debt relief.

Another Brookings study estimated that taxpayers would pay $1.6 trillion to forgive all federal student debt. Relieving $50,000 per borrower would cost about $1 trillion and relieving $10,000 per borrower would cost around $373 billion.

If the administration were to pursue cancellation, it could face a Supreme Court that has struck down some of the administration’s more expansive executive actions.

The administration could take a middle-ground approach by starting a regulatory process, complete with input from stakeholders, to set up a debt-forgiveness program that targets people most in need.

"Administrative agencies have more latitude" with courts when they go through the regulatory process, said Howell Jackson, a Harvard law professor.