A Cheat Sheet for Lawmakers Grilling Jon Corzine: 5 Questions He Should Be Asked

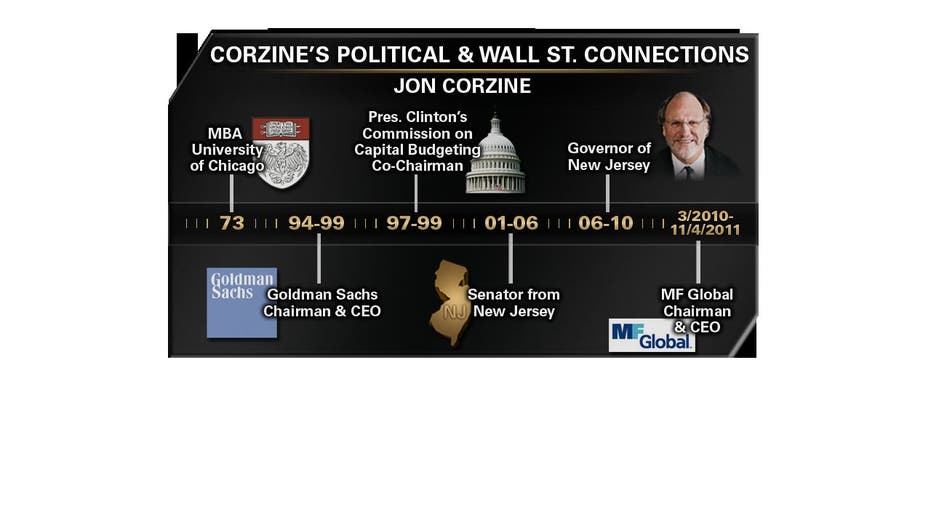

Jon Corzine is no stranger to witnessing tough questions from angry lawmakers grilling someone deemed to have made a major mistake.

The tables will be turned Thursday as Corzine will face a barrage of tough questions about the collapse of his former futures brokerage, MF Global.

If -- and this is a big if -- he chooses to answer questions from the House Agriculture Committee, the testimony will likely be memorable. After all, it’s not every day lawmakers have the opportunity to grill a former U.S. Senator, co-author of Sarbanes-Oxley and outspoken supporter of increased financial regulation about why his company imploded.

Even though Corzine, a former Democratic governor from New Jersey, may see some friends on the panel, he’s unlikely to see many friendly faces.

“My guess is ideology isn’t going to be a big part in this. There’s going to be anger all around because you have a lot of farmers and small businessmen who were hedging and lost money,” said Michael Greenberger, a former director of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission’s division of trading and markets who has testified before this panel in the past.

Rather than play to the cameras and lead a witch hunt, here are five questions lawmakers should ask Corzine if they truly want to get to the bottom of what happened and prevent another MF Global.

1.) When were you first aware that client funds were being used and what type of risk management systems did you have in place to prevent this from occurring?

There’s a good chance that Corzine may not have known that this was occurring or that he may refuse to answer. Legal experts are split about whether Corzine will invoke the Fifth Amendment that protects himself against self-incrimination.

The working theory is that MF Global used the estimated $1.2 billion of missing client funds -- against longstanding rules and principles -- to avoid collapse as customers withdrew cash and counterparties raised margins. Others believe MF Global used the funds even earlier.

The fact that this may have happened has set off alarms in the financial world because it could scare away future investors.

“It cracks the foundation of investor confidence when you can’t trust that a fiduciary is going to segregate client funds from fiduciary funds. It’s a disaster for modern investment management,” said Sean Egan, a founding principal at independent ratings company Egan-Jones.

Duke professor Campbell Harvey said lawmakers should press Corzine on the mechanics of the risk-management systems aimed at preventing so-called co-mingling from happening and demand to know whose responsibility it was for the failure.

“The thing that is most mystifying to people is that what was supposed to be in an untouchable lockbox was tampered with,” said Greenberger, a professor at the University of Maryland. “It’s jeopardized futures trading substantially. It’s put a really black eye on this market.”

2.) As an outspoken critic of excessive leverage in the aftermath of the Lehman collapse, why did you direct your company to go “all in” on a single bet and how did no one stop you?

By some estimates, MF Global’s balance sheet was more leveraged than Bear Stearns' or Lehman Brothers' when they collapsed in 2008. When the full scale of MF Global’s risk -- more than $6 billion in net exposure to euro-zone sovereign debt -- became known, confidence in the company collapsed.

Lawmakers need to understand how Corzine, who wanted to turn MF Global into a mini Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS), got away with it for as long as he did.

“Any firm, in any industry, setting out on such an abrupt new trajectory as [Corzine] chose for MF Global, is a firm that is putting itself in a position of heightened risk for some period of time,” James Gellert, CEO of independent ratings company Rapid Ratings, said in an email. “Did MF Global have the financial strength to undertake this trajectory comfortably?”

“The thing that is most mystifying to people is that what was supposed to be in an untouchable lockbox was tampered with."

3.) How did your coziness with regulators and ratings companies allow you to push the envelope to the point of disaster?

Corzine was so tight with Washington that his name was frequently floated as a successor to Tim Geithner, the secretary of the Treasury Department. Reports have indicated Corzine successfully pushed back for months against calls from regulators to raise more capital to insulate against losses.

Some have speculated Corzine may have benefited from and perhaps even been hired in part because of his close relationship with Gary Gensler, the chairman of the CFTC, MF Global’s primary regulator. The two worked together at Goldman and Gensler reportedly donated to Corzine’s 2005 run for governor.

At the same time, Corzine’s rock-star status may have helped him persuade ratings companies to maintain investment-grade credit ratings on MF Global despite its risky bets. Egan-Jones and Rapid Ratings say they had far lower ratings on the company in the months before its bankruptcy than Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s and Fitch.

4.) Do you think Sarbanes-Oxley is being adequately enforced?

Corzine co-authored this landmark legislation designed to mandate transparency and hold CEOs accountable. However, now that he is in the hot seat, he is likely to claim he didn’t know, or "wasn't aware," MF Global may have broken the law.

While this defense may have worked in the past, Sarbanes-Oxley, which was inspired by the infamous collapse of Enron, was supposed to make it moot by requiring greater accountability.

5.) Does the MF Global collapse weaken the case for moving OTC derivative trading -- such as credit default swaps -- to exchanges or clearinghouses?

The missing client money has wreaked havoc on futures investors like small businesses and farmers. These investors believed their money would be safe in securities traded on regulated exchange like the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (NYSE:CME).

The MF Global collapse comes as regulators rush to install rules mandating CDS be traded on clearinghouses to lower the risk of systemic damage caused by a large-scale default such as one in Europe.

This latest disaster should lead lawmakers to ask Corzine what must be done to prevent losses in the event of a similar event, otherwise investors may have little faith in these new clearinghouses.