Double tap: Investors face taxes for funds that fell in 2018

NEW YORK – As if the worst year for stocks in nearly a decade weren't bad enough, many investors now have to pay a tax bill on top of it.

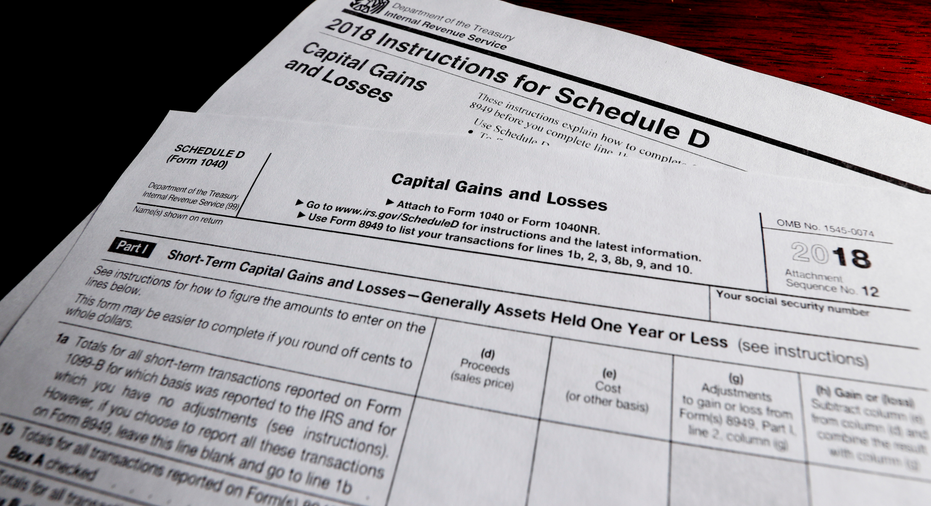

The headache for investors is a result of how mutual funds are structured and how many times the funds' managers bought and sold shares through 2018. Because of the way tax laws work, the majority of investors with a U.S. stock mutual fund or ETF received something called a "capital-gains distribution" late last year.

Investors holding funds in a tax-advantaged account, like a 401(k) or IRA, don't need to worry about it. But if they hold it in a taxable account, watch out. They'll owe taxes on it, due by this spring, and the rate could be as high as 40.8 percent in a few cases. And the last thing many investors want is to pay taxes on something that has already hurt them once: The most popular category of stock mutual fund lost 6.3 percent last year.

"The possible tax hit will add insult to injury," says Frank Pape, director of consulting services at Russell Investments.

Investors can be on the hook for taxes even if they don't sell any shares of the fund themselves. That's because fund managers have to tally up the gains they make each year from buying and selling stocks and bonds, and then pass them on to their investors as capital-gains distributions. Funds make these distributions to all shareholders who own the fund as of a certain date.

This year, the average distribution has been worth 11 percent of the fund's net asset value, according to Russell. That's akin to a fund with a $100 price tag paying out an $11 distribution to shareholders, who are then left with $11 in cash and a fund share that suddenly drops to $89. Shareholders will owe taxes on that $11, and the rate can range from zero for lower-income investors to nearly 41 percent for the highest-income taxpayers if the distributions are categorized as "short-term" gains.

Not only are funds paying out higher distributions — Russell says the 11 percent average payout for this past year is up from 8 percent the year before — more funds are also giving them to their shareholders — 86 percent of all U.S. stock funds, up from 65 percent.

Chief among the reasons is how long this up market for stocks has lasted, even with last year's decline. The S&P 500 hasn't had a 20 percent decline since the spring of 2009, making this the longest-running bull market on record. That means when fund managers sell a stock today, they're likely recording a gain for it.

Also adding pressure is the continued migration by investors out of actively managed funds looking to beat the market and into index funds. Investors pulled a net $301 billion out of actively managed funds last year, according to Morningstar, and managers need to return cash to those shareholders. That can trigger more sales of stocks and bonds, which lead to even more gains.

So, how to avoid these tax headaches? The easiest way is to put your funds into a 401(k) or other tax-advantaged account.

But IRAs and the like come with restrictions on when you can pull out the money. For more flexibility, the industry has come up with a category of investments devoted to minimizing taxes, and they're called tax-managed funds. They trade less often and use other methods to minimize their gains distributions. Index funds can also have smaller distributions than actively managed ones, because they tend to do less trading, but they are by no means immune.

The key thing is not to let the pain of taxes be the No. 1 factor in making a decision. Look for the move that leads to the best after-tax returns rather than the one that has the least taxes.