The woes of Jeffrey Epstein: How he maintained Wall Street connections while downplaying child sex accusations

If New York financier and convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, who was found dead in his Manhattan cell early Saturday morning, was worried that he was about to be arrested on new federal charges of having sex with minors, he didn't really show it.

Leading up to his federal indictment on sex trafficking of underage girls, Epstein had casually brushed off reports about a growing list of victims, a myriad of civil lawsuits and a new federal interest in holding him accountable for the depraved allegations that put him in jail back in 2008.

He told the New York Post in 2011, “I’m not a sexual predator, I’m an ‘offender.’ It’s the difference between a murderer and a person who steals a bagel.”

Later, he explained to a publicist that he had sex with "with 'tweens and teens," according to the New York Times, but rejected the media characterization of him as a "pedophile" who lusted after children.

And when asked to describe the sex acts that landed him in jail a decade ago, he referred to them as "erotic massages," people who know him say. He is said to believe his situation is similar to the mess Robert Kraft, the owner of the New England Patriots, found himself in when he was charged earlier this year for soliciting prostitution in a day spa, FOX Business has learned.

If there were a difference, it was mainly about the location. Kraft paid for sex at a seedy massage parlor in a Florida strip mall; the girls in Epstein's case came to his palatial home in Palm Beach, Florida.

The other difference, of course, is that Kraft's activities involved women, while the charges against Epstein involve underage girls.

The FOX Business Network has spent the past two weeks interviewing various people in Epstein’s orbit. Many didn't want to be quoted by name given the serious nature of the crimes. But according to most of these accounts, the man they knew was nothing like the out-of-control sexual predator who "exploited and abused dozens of minor girls" as depicted by prosecutors in their indictment two weeks ago. They described him as smart, charismatic and generous with his money. He was a gifted investor, and also fun to be around, they said — so fun, in fact, that policymakers, people in high finance, major academics, at least one past president and a former real estate developer who is currently the president took to him for these qualities, as did models and women in the New York-Palm Beach social circuit.

Yet, as they grapple with his downfall, looking to rationalize the man they knew with the sexual predator they have read about, there is one personality trait that stands out, and may explain Epstein's downfall: An immense self-confidence — a cockiness — in his ability to succeed at just about anything.

This trait might explain why, despite humble beginnings, Epstein was able to achieve success in the rarefied world of high finance, having accumulated a net-worth of at least $500 million. It explains how he was able to attract A-list friends and associates in politics and academia at the citadel of Ivy League prestige, Harvard University, without ever earning a college degree. It might also explain why he chose to gamble with his private life so much that he thought he could avoid scrutiny, even while, as prosecutors allege, engaging in illegal sexual acts.

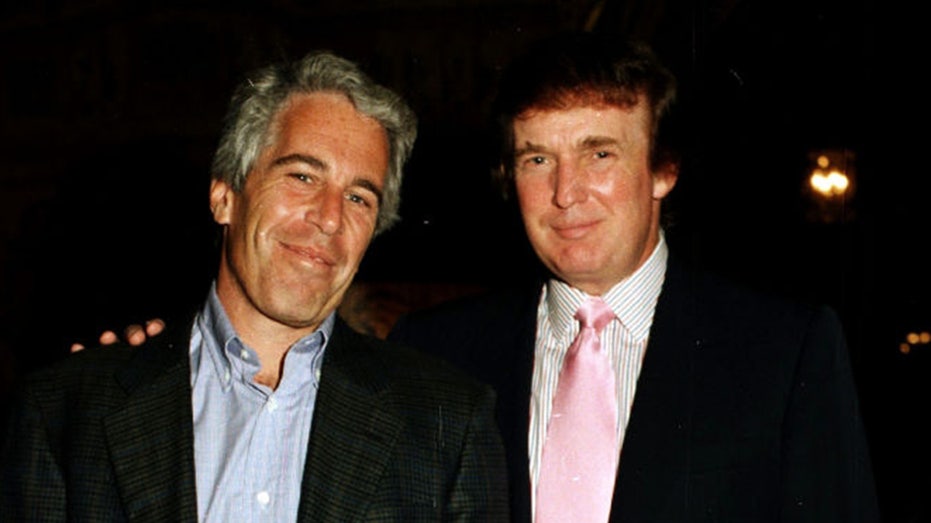

Portrait of American financier Jeffrey Epstein (left) and real estate developer Donald Trump as they pose together at the Mar-a-Lago estate, Palm Beach, Florida, 1997. (Photo by Davidoff Studios/Getty Images)

It could also be why, amid a recent drumbeat of intense media and legal scrutiny over his 2008 plea deal, Epstein chose to come back to the U.S. from France two weeks ago, only to be arrested at Teterboro Airport in New Jersey as he got off his private jet to face new federal charges of child sex trafficking. France, after all, is a country with such weak extradition laws that for decades it harbored filmmaker and convicted child rapist Roman Polanski.

"It is mind-boggling," his former attorney, Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz told FOX Business. "France probably wouldn't extradite him, and he has wealth. It's possible he thinks he can beat the case."

Dershowitz was part of the high-powered legal team that convinced federal prosecutors they should drop most of their case against Epstein in 2008, after investigators uncovered allegations that he performed sex acts with numerous underage girls at his estate in Palm Beach. Epstein spent only 13 months in jail for sex with a minor and soliciting a prostitute on state charges — not the more serious federal charges — because his lawyers convinced prosecutors the initial case was weak enough that he might prevail at trial. Epstein then sought to reassemble his life and business activities even as a registered sex offender, albeit one with friends in very high places.

Those friends initially accepted Epstein back into their world; he was seen dining with various Wall Street executives at New York power restaurants, FOX Business has learned. He rekindled his association with the British royal family, most notably once again hanging out with Prince Andrew. He began to return to the New York-Palm Beach party circuit attended by various celebrities. He did business with some of the biggest names in finance even as he became the target of numerous lawsuits by new alleged victims, and received media attention as the "convicted pedophile" Jeffrey Epstein.

It is very possible Epstein will never see the light of day again.

But in recent months, Epstein's past could not be ignored by his powerful friends and associates as his seemingly lenient sentencing received fresh attention following a series of reports in the Miami Herald that uncovered possible missteps in the prosecution, and an array of new alleged victims attesting to abuse. Prosecutors then sought new ways to reopen the case as a federal crime when they say they discovered credible evidence that Epstein had in fact engaged in sex acts with minors not just in Florida, but in New York and elsewhere between 2002 and 2005, culminating in his indictment earlier this month.

Epstein has pleaded not guilty to the new charges brought by the U.S. Attorney's office for the Southern District of New York. His lawyers have referred to the new case as a "do over" of the previous one. But he was recently denied bail and will continue to be housed during his trial at the federal lockup in lower Manhattan; his new home is a far cry from his posh New York City townhouse. The Manhattan Detention Center is known for its harsh conditions and housing of hardened criminals, such as mafia kingpins and Mexican drug lord Joaquín 'El Chapo' Guzmán. The conditions are so difficult, that police believe Epstein reportedly tried unsuccessfully to commit suicide.

A police raid on his Manhattan townhouse uncovered photos of what "appear to be of underage girls, including at least one girl who, according to her counsel, was underage at the time the relevant photographs were taken,” prosecutors said, possibly leading to more charges. Epstein currently faces 45 years in jail, and given the Southern District's extremely high percentage of conviction rates, he is likely to serve all of them — or as Dershowitz put it, "It is very possible Epstein will never see the light of day again."

Epstein's current attorney, Reid Weingarten, declined to comment on this report.

RAGS TO RICHES

Epstein certainly needed a degree of hubris to go from college dropout to multi-millionaire investor with friends in very high places. He grew up in a working-class family on Brooklyn's Coney Island, the son of a New York City Parks and Recreation employee. He graduated high school early, attended college briefly, but dropped out to take a job as a math teacher at the prestigious Dalton School in Manhattan, where he was known as a charismatic, occasionally talented and often undisciplined instructor.

Epstein's teaching style got him booted from Dalton in 1976, but his smarts got him his first job on Wall Street at Bear Stearns, the brokerage firm then run by the legendary trader, Alan "Ace" Greenberg. One of Epstein's students was Lynne Greenberg, who told her dad that Epstein might make a great financier. It was an unorthodox entry into Wall Street, an industry which often recruits from top schools, but Bear Stearns was an unorthodox firm - one that would be his go-to investment bank for much of his career in finance.

Under Greenberg, Bear Stearns earned a reputation as a scrappy, working-class competitor to elite investment banks like Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs. Greenberg often said that his best hires were known as "PSDs" — shorthand for poor, smart and determined. Greenberg died in 2014, and his daughter didn't respond to a request for comment, but former Bear executives say the culture of the place rewarded risk taking and making money, and Epstein grasped this ethos immediately.

Management at Bear believed Epstein's sharp mind would make him possibly a great trader and high-end broker dealing with rich clients. He started out at the firm as an assistant to a floor trader, and soon began working with wealthy clients on bigger projects that sought an edge in esoteric markets, according to people with direct knowledge of the matter.

But Epstein's accumulated knowledge of the U.S. tax codes — and how rich people can avoid taxes through various investments — made him one of Bear's prized assets in its small, but specialized brokerage department, a former senior Bear Stearns executive said.

By 1980, he was named a limited partner and as one of the company's top executives, entitled to a bigger share of Bear's bonus pool, then among the biggest on Wall Street. These year-end payouts were worth multiple millions of dollars and would make Epstein a rich man just a few years after leaving Dalton and his skimpy teacher's salary.

"He never went to college, but he knew everything about taxes," the senior executive said. "In fact, he could figure out just about anything if he studied it. The guy was a genius."

This executive said Epstein's sex life was never an issue at the firm, but something else was. Just one year after making it big at Bear, he left, albeit quietly. The senior executive said Epstein "left at our invitation ... it was very serious stuff."

Even inside Bear — a place that accepted sharp elbows — Epstein was seen as controversial. He clashed with some of the firm's partners and was said to stretch various trading and investing rules.

Despite reports over the years that Epstein was embroiled in an investing dispute, the executive insisted the incident that eventually triggered his ouster from Bear involved a significant expense account violation concerning an airline ticket that upper management was misled about. The executive declined to elaborate, and Epstein's attorney didn't return a call for comment.

Not all of Bear's management wanted him out. Greenberg's No 2, James "Jimmy" Cayne remained fond of and impressed with Epstein’s investment acumen and how he worked with clients. So while Epstein's infraction was enough to get him booted as an employee of Bear, he maintained his relationships with top executives at the firm for the next 30-plus years. Those relationships were so strong that years later when Epstein began to make a name for himself, and reporters began to question why he left the firm, Bear officials said it was because he wanted to start his own money management firm.

That money-management business, contrary to many media reports, was not a hedge fund, which is essentially a mutual fund that is allowed to take more risk because it caters to wealthy individuals. Operating a hedge fund would have been beneath Epstein because it would have forced him to go out on client pitches and beg for business, people who know him say. Another drawback: Such investments are loosely regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission and would have opened Epstein, a temperamentally secretive man, to a high degree of scrutiny (Epstein has been called many things since his conviction but he has been known to remark that being referred to as a hedge fund manager is among the worst, according to a person with knowledge of the matter).

Either way, Epstein brushed aside his issues at Bear, and went to work building a money-management business. He fancied himself as a free-wheeling investment adviser and banker for select clients, people familiar with him say. His investment activities were barely mentioned in the press during these years, and Epstein liked it this way. His main money management firm, Financial Trust Co., has left a scant paper trail, but people who worked at Bear during the 1980s, 1990s and into the 2000s say Epstein did significant business with and through the firm for clients, but most notably Leslie Wexner, the billionaire founder of The Limited (now known as L Brands, Inc.), the retailer that owns Victoria's Secret, among other retail brands.

By most accounts, Epstein met Wexner sometime after he left Bear when he was snooping for rich clients in Palm Beach, Florida, the home and second home of numerous millionaires and billionaires (Palm beach would later become Epstein's own second home when he achieved similar income and status). Former Bear Stearns executives recall that Epstein spent the vast majority of his time when he dealt with the firm working on Wexner matters; he frequently traded on behalf of Wexner and The Limited through Bear's block-trading desk, an area of the firm that specialized in larger orders for Bear's best customers. Epstein also used the firm's research in his investment ideas, former executives say (a spokesman for Wexner declined to comment, but would not deny the matter).

Epstein's wealth was clearly growing, albeit quietly. He was now easily a multimillionaire on his way to earning many millions more, and became a high-net-worth client of Bear Stearns' brokerage operations. Instead of Epstein cold-calling rich people hawking trading ideas, he was on the receiving end of the pitch. It was around this time that Epstein developed another significant business relationship: This one with Steven Hoffenberg, the flamboyant head of Towers Financial Co., which in the mid-1990s briefly owned the New York Post.

An association with Towers was an odd fit for a man eventually associated with Harvard academics and big-time financiers like Wexner. Towers was a pedestrian bill-collecting company that during the mid-1980s takeover mania morphed into a second-tier corporate raider with the help of Epstein, Hoffenberg told FOX Business.

Hoffenberg said that he and Epstein were partners for about eight years, and did some of their takeover business with the assistance of people at Bear Stearns, though "not a lot." And good thing for Epstein's pals at Bear: In a few years, federal prosecutors would determine that Towers was also a Ponzi scheme that sold bonds to investors to replace money Hoffenberg was stealing.

At his core, Epstein has no moral compass. He has no moral compass, whether it comes to money or little girls.

In an interview, Hoffenberg described Epstein as his "co-conspirator" in that theft. He said he fired Epstein in the early 1990s because "he was stealing too much. I couldn't supervise him."

By 1995, Hoffenberg was headed to jail for 18 years, convicted of defrauding investors out of $450 million in one of the largest pre-Bernie Madoff Ponzi schemes. Epstein was not charged in the case. After leaving prison, Hoffenberg sued Epstein for his alleged role in Towers' fraud. The lawsuit was dismissed.

"At his core, Epstein has no moral compass," Hoffenberg said. "He has no moral compass, whether it comes to money or little girls."

When asked if he is currently cooperating with federal authorities as they dig deeper into Epstein's private and business life, Hoffenberg said: "I wish I could tell you."

SOCIETY MAN

The 1990s were a glorious time to be Jeffrey Epstein, as the financier easily moved on from Hoffenberg as if his relationship with the convicted con man never happened. His job description, according to press reports, was "President of the Wexner Companies," and by now Wexner was a super-rich American businessman and philanthropist worth more than a billion dollars.

This relationship would confer both wealth and prestige on Epstein, who immersed himself in Wexner's private and professional lives. He bought a home in Columbus, Ohio, where Wexner's companies were headquartered and began managing not just Wexner's vast wealth, but also various charities and some personal affairs. While it's unclear how much actual day-to-day management authority of L Brands Wexner gave Epstein, he had compensated Epstein enough to help the former Dalton math teacher purchase a private jet (a Boeing 727), residences in two states, and a lifestyle of partying with the likes of Donald Trump at Mar-a-Largo, the then-real estate developer's Palm Beach estate, not far from Epstein's own sumptuous home that he bought in 1990 for $2.5 million.

Epstein also knew how to buy some of his high-powered connections. According to a New York Times piece in 1992, Epstein gave $2 million, along with Wexner and other benefactors, to finance a building at Harvard University for the Harvard-Radcliffe Hillel Foundation, the school's Jewish student organization. It would be the start of a long and somewhat controversial relationship with the university that allowed Epstein not just to put a positive spin on his wealth, but created an air of respectability with major players in politics and public policy.

Epstein soon joined the Council on Foreign Relations, a prestigious think tank with members plucked from the top of academia and finance, and affixed himself to Rockefeller University's board of Trustees in 1995, touted by the college in a press release that described Epstein's academic credentials as having "studied physics at Cooper Union."

But it was an association with Harvard that Epstein showed the most passion for. During the 1990s, Epstein plowed millions of dollars to fund various projects sponsored by the school, mainly in math and the sciences, and could be seen roaming around on or near the campus dressed casually in jeans and a Harvard hoodie. Epstein established his own office just off campus, which served as a base of operations for his Harvard activities, including what has been described as a mini-lecture series where he invited school faculty to discuss various public policy and scientific matters, Dershowitz told FOX Business.

Among those who participated was then-Harvard president and former Clinton administration Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, and David Gergen, a former adviser to presidents and currently a professor at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government, in addition to Dershowitz, FOX Business has learned. A spokeswoman for Summers confirmed that he had participated in what she described as "Harvard sponsored" discussions that Epstein hosted. A spokesman for Gergen had no comment. Harvard declined to comment.

Dershowitz said he met Epstein through a mutual friend in the mid-1990s and the relationship, as described by Dershowitz himself, was formed over discussions about weighty intellectual matters but morphed into a more professional connection. In addition to his work as a practicing lawyer and Harvard professor, Dershowitz is a well-known public intellectual who has authored 40 books of both fiction and non-fiction, many of them making best seller lists. He said he was so impressed with Epstein's raw intellect that he had him provide a pre-publication critique of a couple of his books over the years.

Later, Epstein would turn to Dershowitz as a key member of the legal team that crafted the plea deal in 2008 for the sex crime. Dershowitz would also pay a price for this association when he was accused in a lawsuit this year of having sex with one of Epstein’s alleged victims nearly 20 years ago. Dershowitz has denied the matter and says he has evidence to back up his innocence.

Looking back on those years, Dershowitz described Epstein this way: "He was brilliant," he said, adding that the notion Epstein's private life involved sex with young girls would have shocked the growing list of power players in the Harvard orbit Epstein associated with.

"That stuff just never came up, never," Dershowitz said.

It's unclear how exactly Epstein's Harvard ties helped him in the financial business, but they certainly didn't hurt. He continued to do money-management business using Bear Stearns as his main Wall Street broker, but now his dealings also involved JPMorgan, one of the nation's biggest banks, people at the financial institution told FOX Business. A spokesman declined to comment, but people there say the relationship ended in 2013.

Hoffenberg said he believes most of Epstein's clients during this time were wealthy Europeans, while the former Bear executive said he had a number of uber-rich American businessmen seeking Epstein's expertise in tax avoidance.

Several of those American businessmen denied having any association with Epstein, even if he was spending money like he was making it in vast quantities. In 1996, Epstein told the New York Times that he had become the owner of Wexner's elegant East 71st Street Manhattan townhouse, which featured a "bathroom reminiscent of James Bond movies" that was "hidden beneath a stairway, lined with lead to provide shelter from attack and supplied with closed-circuit television screens and a telephone." The sidewalk in front of the mansion was heated so snow and ice wouldn't accumulate in the winter.

Wexner reportedly purchased the home in 1989 for $13.2 million. Press reports have also suggested that Wexner may have gifted the house to Epstein for free, but a representative for Wexner told FOX Business that Epstein paid $20 million for it in 1998. It's currently worth around $70 million.

Epstein also began to spread money around, politically, contributing tens of thousands of dollars, mostly to prominent Democrats like Senate Minority Leader Charles Schumer, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, which tracks donations (Schumer has since donated those political contributions to charity, an aide told FOX Business). Another recipient of this largesse was former President Bill Clinton. Epstein had been donating money to the White House Historical Society during the Clinton terms, and the two remained chummy for years, even after the president left office and started his Clinton Foundation charity.

In 2002, the New York Post's widely read Page Six gossip column caught on to the Epstein power scene, reporting that Clinton – out of office less than two years – and actors Kevin Spacey and Chris Tucker, accompanied Epstein on his private plane for a trip to Africa, presumably on Clinton Foundation business.

"How Clinton, who took off on Saturday, hooked up with his traveling companions is a mystery - as is his relationship to Epstein," the Post reported. "Little is known about Epstein except that his offices are in the land-marked Villard House across from Le Cirque, and he once employed Ghislaine Maxwell, daughter of the late British press lord Robert Maxwell, in an unspecified capacity."

Maxwell would figure prominently in Epstein's life for years later. She was said to be Epstein's one-time girlfriend and then long-time associate, and given her vast social network, the person who connected Epstein with various power players such as Prince Andrew and Clinton. Maxwell was also accused in civil suits of arranging Epstein's trysts with underage girls, charges she has denied. Maxwell has not been charged by state or federal authorities in the matter and she could not be reached for comment.

But the Page Six piece brought significant attention to Epstein from the mainstream media in ways he never imagined. The once-secretive Epstein seemed to relish the publicity possibly too much, as reporters for the first time truly began to pry into his business, and now, personal life.

In 2002, New York Magazine published a lengthy and mostly positive profile on Epstein titled "Jeffrey Epstein: International Money Man of Mystery," that discussed his various high-profile relationships, and in vague terms, his money-management business that was said to have $15 billion in assets under management, equivalent to a large hedge fund. It quoted, almost prophetically, Trump describing Epstein this way: "I've known Jeff for fifteen years. Terrific guy. He's a lot of fun to be with. It is even said that he likes beautiful women as much as I do, and many of them are on the younger side. No doubt about it, Jeffrey enjoys his social life."

Epstein, in 2003, also cooperated for a piece by Vanity Fair's Vicky Ward. Like the New York Magazine piece, the lengthy profile described Epstein's secretive investment activities and his vast social network, but that's where the similarities end. Ward began her research into Epstein after the Page Six piece. She suspected Epstein planted the New York Magazine article to blunt some of her own tough reporting that filtered back to Epstein.

Ward was skeptical of the breadth of his client list and wealth; her reporting included, for the first time, Epstein's connections to Hoffenberg as well as sordid details of Epstein's personal life that had never been published before.

Ward tells FOX Business she obtained fully sourced allegations that Epstein committed sexual assault against one woman and one underage girl. Both were on the record including the mother of one of the alleged victims. Epstein fought hard to get this part of his private life removed from the piece. Eventually, the section was edited out of the final copy after Epstein protested to Ward's editor, then Vanity Fair boss Graydon Carter, Ward told FOX Business.

Vanity Fair declined to comment, but a spokeswoman for Carter, who is no longer with the magazine, denied some details of Ward's account of the editing process.

"It's absolutely untrue that Vicky had three girls on the record," the spokeswoman said. "No one was on the record saying they had underage sex with Epstein. One person was on the record about Epstein wanting to have sex, but wasn’t actually sexually assaulted."

Either way, Epstein's dirty little secret remained out of the press, but not for long.

THE COLLAPSE

In 2005, Epstein's web of relationships spanned from business, finance, academia, public policy and to the top of the top players in national politics. His relationship with Harvard, Bill Clinton and Wexner appeared as strong as ever. At Bear Stearns, Ace Greenberg had relinquished his day-to-day management role. But Jimmy Cayne developed a strong bond with Epstein, who continued to do business with the bank. In addition to residences in New York and Palm Beach, he had a ranch in New Mexico and owned a private island in the Caribbean.

At the urging of senior Bear executives, Epstein invested tens of millions of dollars in a hedge fund tied to the mortgage market, according to one person with knowledge of the matter. The fund, at least for a time, became one of the best performers on Wall Street and earned Epstein a tidy profit. Epstein also had developed a fairly close relationship with Leon Black, the billionaire financier who was head of the private equity powerhouse Apollo Global Management, using his expertise on taxes to advise Black on various transactions, according to a report in the New York Times.

But the same allegations that Ward came across about Epstein and underage girls also resurfaced in a major way. Palm Beach police raided Epstein's estate after hearing allegations he had sex with an underage girl. During the investigation, the list of minors that police found alleged to be providing Epstein with what was referred to as "erotic massages" at the compound began to grow well beyond anything that Ward's reported had uncovered.

Soon, a federal grand jury was impaneled and the FBI launched a wide-ranging investigation into the matter for the possible sex trafficking of minors.

In 2007, the feds drew up a 53-page indictment; it appeared Epstein was headed to jail for a long time because of harsher federal sentencing guidelines. But even as the sordid details began to appear in the press, Epstein characteristically held fast. He maintained his innocence and gambled that a coterie of high-powered lawyers, including former independent counsel Kenneth Starr, Dershowitz, Roy Black, and a Palm Beach attorney named Jack Goldberger could make the case, or at least most of it, go away.

Epstein's legal bills were enormous – well into the millions of dollars, said a person with direct knowledge of the matter. He was losing another chunk of money in that Bear Stearns hedge fund that was tied to the increasingly depressed national real estate market. Bear was the first firm that collapsed in the 2008 financial crisis. A harbinger of its collapse was the implosion in 2007 of a couple of its hedge funds that invested client money in risky mortgage-backed securities – the same investments that doomed the firm a year later.

FILE - In this July 30, 2008 file photo, Jeffrey Epstein, center, appears in court in West Palm Beach, Fla. The wealthy financier pleaded not guilty in federal court in New York on Monday, July 8, 2019, to sex trafficking charges following his arrest

Epstein had invested about $60 million into the fund, making him one of its largest investors, former Bear executives tell FOX Business. With the sex abuse case moving forward, Epstein certainly had bigger issues to worry about but he was so livid at his losses that he instructed his representatives to meet with a group of other investors and considered joining them in litigation against Bear, according to two people with direct knowledge of the matter.

Hedge fund investors are technically limited partners of the fund run by an investment manager, in this case, Bear Stearns. Those partners can gain control of the fund by assembling 51 percent of investors and voting for a takeover as the investment manager. That was the plan proposed to Epstein in the summer of 2007, according to a person with direct knowledge of the matter.

The takeover would grant access to confidential documents about the fund so the investors could show that the firm misled them about its risks and failing performance in the run-up to its demise, said the investor who was part of the legal action. If the investors could prove fraud, Bear might not be able to survive the resulting litigation that could result in billions of dollars in damages.

In late 2007, Epstein was said to be interested in joining the litigation, his lawyers told the investing group. He was an important addition: Without him, the group would not make the necessary 51 percent threshold.

"We were heading to the meeting at Bear headquarters for a meeting feeling great when we heard the news that Epstein was out," said one of the investors who spoke to FOX Business on the condition of anonymity. "It was a huge letdown. The whole effort fizzled."

In months, the investors understood why Epstein needed to move on with his life: Epstein lawyers were about to craft a lenient plea deal with then-U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Florida, Alex Acosta - a Houdini-like move - that reduced Epstein's jail time from possibly decades to no more than 18 months on state, not more serious federal charges. Among other remedies such as victim restitution, Epstein would have to register as a sex offender. He ended up serving just 13 months.

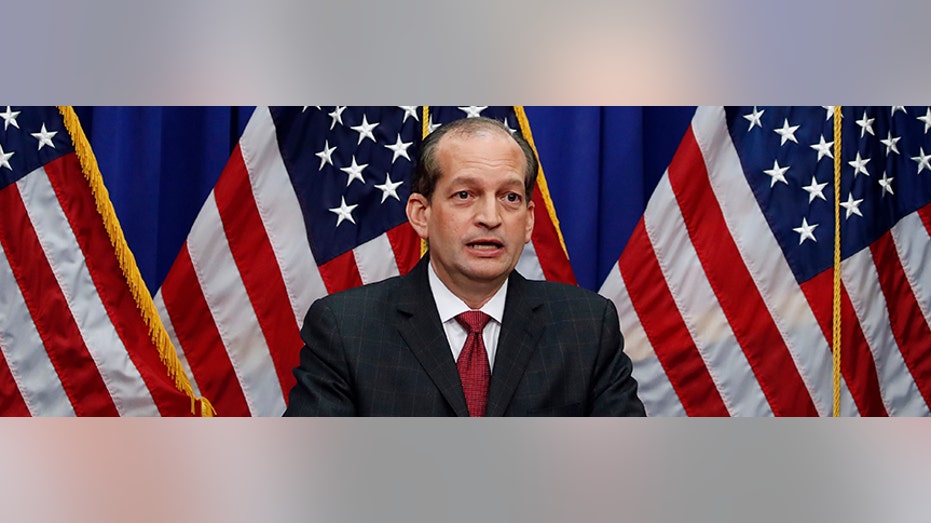

The terms, meanwhile, were kept secret from the victims. Acosta, who recently stepped down from his job as Trump's labor secretary amid the smoldering controversy over the arrangement, declined to comment to FOX Business. But a person close to him reiterated what Acosta has said publicly about the matter, particularly during his confirmation hearings for the job with the Trump administration. Namely, the federal case was weak because there was a lack of evidence that the victims were transported across state lines, while others were said to have made poor witnesses. This person said the terms, however lenient, were vetted by the Justice Department.

As Epstein was headed to spend several months in jail during the summer of 2008, Wall Street was heading toward armageddon. Bear Stearns had already collapsed, and another bank, Lehman Brothers, was on its way, touching off a massive federal bailout of the rest of the banking system. A theory emerged that the financier's light sentence for a fairly explosive crime was the result of his broader cooperation in a federal criminal case against the hedge fund managers – and Wall Street itself – in the aftermath of the crisis.

The mysterious and brilliant Epstein, who knew where all the Wall Street bodies were buried, used his vast knowledge of the financial world to escape again, or at least that was the rumor that found its way into several news reports.

But Ralph Cioffi and Matthew Tannin, the managers of the Bear Stearns hedge fund who were indicted for securities fraud, were also acquitted. During the Feds’ post-crisis crackdown on Wall Street, not a single CEO of a bank was indicted. The theory of Epstein helping with any Wall Street case turned out to be an urban legend, a FOX Business investigation showed. Prosecutors and Epstein’s own lawyers said he never aided in any post-crisis prosecution.

If Epstein's time in jail was uneventful, his release in 2009 wasn't. Civil lawsuits from new alleged victims began to pile up almost immediately; the Palm Beach Post, the local newspaper of his Florida residence, sued to get the details of the lenient plea deal with the federal government unsealed.

Epstein scrambled to settle some of the victim lawsuits and fought others, including one that requested the court approve the examination of his penis. The press attention continued, however. Epstein was forced to reveal his wealth in one court document as over "nine figures" or approaching a billion dollars. No longer was he referred to as the "mysterious billionaire Jeffrey Epstein." Now newspapers covering the allegations by alleged victims referred to him as "convicted pedophile Jeffrey Epstein." His jet was dubbed "The Lolita Express."

Despite this, Epstein plowed ahead and began to reassemble his post-jail social and business life as if he served time for traffic violations. Gossip columns reported him spending time with Prince Andrew at his New York mansion. The news that embarrassed the royal family was compounded when it was revealed that Epstein gave the prince's ex-wife, Sarah Ferguson, money to pay off a debt. Prince Andrew and Ferguson did not respond to requests for comment.

He sought to downplay his legal troubles as a mistake, and in conversations, maintained he did not have a sexual attraction to children, according to people with knowledge of the matter. He referred to the press coverage of additional alleged victims as the work of zealous plaintiff attorneys looking to cash in on his wealth and notoriety, those sources said.

And for a time, Epstein was accepted back into high society and high finance. Bear Stearns was no longer in existence when he was released from jail, so Epstein did most of his banking through JP Morgan. The nation's largest and most prestigious bank, known for its risk controls that helped it escape the ravages of the financial crisis, had no problem opening its doors to the ex-con with hundreds of millions of dollars at his disposal.

In 2011, the Manhattan district attorney's office came to Epstein's aid and sought to reduce his sex-offender status from the highest level (Level 3) to the lowest level (Level 1). A judge denied the request. Epstein, meanwhile, maintained his business relationships with Leon Black, and at least one former top executive at JPMorgan, James Staley, who was considered a possible replacement to long-time CEO Jamie Dimon before he left the bank to take over as CEO of Barclays.

Staley, JPMorgan and Black had no comment.

Epstein's reinvention, however, couldn't overcome the #MeToo movement, which brought new and renewed scrutiny to his lenient sentencing for sex crimes. Acosta, the former U.S. Attorney who arranged the plea deal, immediately came under fire when he was named Trump's labor secretary. During his Senate confirmation hearing, he was grilled about the Epstein case during

Labor Secretary Alex Acosta answers a question during a news conference at the Department of Labor, Wednesday, July 10, 2019, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

He resigned from the post in mid-July, not long after Epstein's indictment.

Late last year, the Miami Herald launched an investigation into the sentencing with new and explosive details about alleged victim abuse, which instigated a new federal investigation into the decade-old case. Finally, prosecutors had evidence showing he engaged in a multi-state crime that carried with it harsher, federal penalties.

Epstein's business associates began to publicly renounce their association with him. Wexner had already dropped Epstein just after his arrest in 2008, but now his representatives made it official.

JP Morgan stopped doing business with Epstein in 2013, and Epstein turned to the loosely regulated Deutsche Bank to handle his investments and trading.

But even Deutsche Bank, which had been the target of a federal probe into money laundering and was known for its weak risk controls, also cut ties with Epstein as the controversy swelled (A Deutsche Bank spokesman declined to comment).

The hardest critiques came from Epstein's old friends. Back in 2002, after traveling on Epstein's private jet, Clinton referred to the financier in the New York Magazine piece as "both a highly successful financier and a committed philanthropist with a keen sense of global markets and an in-depth knowledge of twenty-first-century science."

After Epstein's arrest this July, Clinton, through a spokesman, described the relationship this way: "In 2002 and 2003, President Clinton took a total of four trips on Jeffrey Epstein's airplane: one to Europe, one to Asia, and two to Africa, which included stops in connection with the work of the Clinton Foundation. He's not spoken to Epstein in well over a decade, and he has never been to Little St. James Island, Epstein's ranch in New Mexico, or his residence in Florida."

A spokesman for Clinton didn't respond to a call or email for comment.

President Trump couldn't resist taking a shot at the guy he was once so fond of for their mutual admiration of women.

"(I) knew him like everybody in Palm Beach knew him," the president said during a press conference. "I had a falling out with him. I haven't spoken to him in 15 years. I was not a fan of his, that I can tell you."

Wexner, through L Brands, has now put out a terse statement to employees adding a different spin to his decades-long ties to Epstein. "While Mr. Epstein served as Mr. Wexner's personal money manager for a period that ended 12 years ago, we do not believe he was ever employed or served as an authorized representative of the company," the company said

These remarks were hardly surprising to Epstein who brushed them off, as if he will somehow emerge on top despite his prominent detractors, people who know him say as. After all, he is said to believe these were the same people who, up until recently, thought he was such a great guy.