McDonald's, Chipotle and Domino's feast during COVID-19 while your neighborhood restaurant fasts

Big, well-capitalized chains are gaining customers and adding stores while tens of thousands of local eateries go bust

The coronavirus pandemic is splitting the restaurant industry in two. Big, well-capitalized chains like Chipotle Mexican Grill Inc. and Domino's Pizza Inc. are gaining customers and adding stores while tens of thousands of local eateries go bust.

Larger operators generally have the advantages of more capital, more leverage on lease terms, more physical space, more geographic flexibility and prior expertise with drive-throughs, carryout and delivery. A similarly uneven recovery is unfolding across the business world as big firms have tended to fare far better during the pandemic than small rivals, thinning the ranks of entrepreneurs who could eventually become major U.S. employers. In the retail world, bigger chains like Walmart Inc. and Target Corp. are posting strong sales while many small shops struggle to stay open.

The divide between large and small restaurants surfaced in the summer. Chipotle more than tripled its online business sales in the second quarter while Domino's, Papa John's International Inc. and Wingstop Inc. all reported double-digit same-store sales increases in the third quarter compared with the year-earlier period. McDonald's also said U.S. same-store sales rose 4.6% in the third quarter. That included a rise in the low double digits during September, its best monthly performance in nearly a decade. It credited faster drive-throughs and promotions.

Customers dine outside McDonald's in New York City. (Photo by Noam Galai/Getty Images)

MCDONALD’S REPORTS QUARTERLY BOOST FOLLOWING TRAVIS SCOTT PARTNERSHIP, SPICY NUGGETS RELEASE

Many other big restaurant companies took additional steps to take advantage of the shift to takeout. Brinker International Inc.'s Chili's division pushed up the summer debut of a delivery-only brand, Just Wings, that it expects to generate more than $150 million in sales in its first year.

"The silver lining in this pandemic is we are going to emerge stronger," said Bernard Acoca, chief executive of El Pollo Loco Holdings Inc., a chain of 475 Tex-Mex restaurants across the Southwest. El Pollo has opened three restaurants in 2020 and aims to add more in years ahead, he said.

The prospects for many independent restaurants, meanwhile, are getting dimmer. Three-quarters of the nearly 22,000 restaurants that closed across the U.S. between March 1 and Sept. 10 were businesses with fewer than five locations, according to listing site Yelp.com.

Frequent closings have always been a facet of the restaurant business. Restaurants typically run on slim margins. Some 60,000 restaurants open in an average year, according to the National Restaurant Association, and 50,000 close.

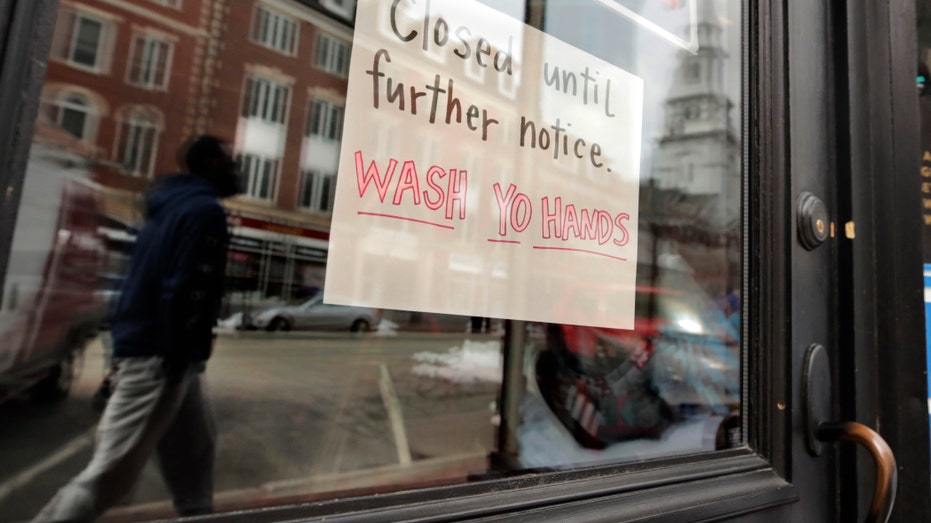

A closed sign hangs in the window of a shop in Portsmouth, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa, File)

MCDONALD'S ADDING ITEMS TO MCCAFE MENU FOR FIRST TIME IN NEARLY A DECADE

But this upheaval is the most profound in decades. The association predicts 100,000 restaurants will close this year. The sudden loss of many independent restaurants could permanently alter the landscape of American cities. Some chefs and restaurant operators fear the recent revival of downtowns across the country will slip into reverse.

Employment at restaurants and bars has dropped by 2.3 million jobs from a total of more than 12 million before the pandemic, according to the Labor Department. In fact, the broader leisure and hospitality sector experienced the largest total drop in employment since February in a major industry.

The pandemic will wipe out $240 billion in sales this year, according to a projection from the National Restaurant Association, a trade group. Last year, the industry brought in more than the agriculture, airline and rail-transportation industries combined, according to Bureau of Economic Analysis figures.

Getting Bolder

The pandemic hasn't spared all big chains.

Many casual-dining companies have posted double-digit sales declines. More than a dozen companies have filed for bankruptcy protection, including Ruby Tuesday Inc. and California Pizza Kitchen. Shake Shack Inc. and Ruth's Hospitality Group Inc. returned millions of dollars of federal aid meant for smaller businesses hurt by the coronavirus pandemic. Starbucks Corp., Dunkin Brands Inc. and Pizza Hut said they are planning to close 1,500 stores between them in the next 18 months.

Yet many other chains say now is a time to get more aggressive. Olive Garden's parent, Darden Restaurants Inc., is looking into expanding in urban areas including Manhattan where rents were previously too expensive to justify growth. Plenty of space is opening up: 87% of 450 restaurant bars, and clubs in New York said in a recent survey that they couldn't pay their full rent for August, according to the NYC Hospitality Alliance.

Starbucks, while closing some locations, plans to spend $1.5 billion during its current fiscal year partly to add 800 stores in its American and Chinese markets, speeding a shift to restaurants that emphasize drive-throughs and pick-up counters. Darden plans to spend $300 million by mid-next year, a chunk of it to add 40 new restaurants. Papa John's franchisee HB Restaurant Group LLC plans to open dozens of shops and Wingstop said it added 43 restaurants in the quarter ended in September.

"There is no better time than now to get bold," Wyman Roberts, Brinker's chief executive, said in an interview.

Some customers have already moved more spending to chain restaurants in ways they say they expect to last beyond the pandemic.

A Pizza Hut restaurant stands in Munfordville, Kentucky (Luke Sharrett/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

163 PIZZA HUT RESTAURANTS UP FOR SALE AFTER FRANCHISEE FILES FOR BANKRUPTCY

Joyce Hill, a 52-year-old professor at the University of Akron in Ohio, said she has been ordering more from Cracker Barrel Old Country Store Inc. and Bloomin' Brands Inc.'s Bonefish Grill and Carrabba's Italian Grill divisions. She said she intends to stick with chains because it is easier and she doesn't feel safe eating inside restaurants.

"With a few clicks, I can order a whole meal, pay for it, and not have to leave my car to pick it up," said Ms. Hill. She said she recently stopped by a local Mexican restaurant for shrimp tacos after not visiting for months. It was closed.

One restaurateur benefiting from this shift is Tabbassum Mumtaz, the operator of 400 KFC, Long John Silver's, Pizza Hut and Taco Bell restaurants in nine states. Things didn't look good at first. He shut all of his dining rooms after the pandemic intensified in the spring, and his sales, typically about $500 million a year, fell by an average of 25%.

But he said he shifted many of his 10,000 employees to cleaning and staffing drive-throughs -- which he said became the core of his business.

"Everyone was of one rhythm," said Mr. Mumtaz, owner of Richardson, Texas-based restaurant operator Ampex Brands LLC.

Mr. Mumtaz said his cash balance improved around April after parent company Yum Brands Inc. deferred the 5% royalty payments he owed for several months. Yum introduced promotions for bigger family deals, such as $30 buckets of KFC chicken, to help boost sales as customer counts remained low.

Yum introduced promotions for bigger family deals, such as $30 buckets of KFC chicken, to help boost sales as customer counts remained low. (iStock)

Some landlords provided rent breaks and his three banks agreed to let him pay only interest on loans, suspending principal payments. Mr. Mumtaz also received a Paycheck Protection Program loan valued at more than $5 million in April to help retain 500 jobs, according to federal figures. He said he used the money to avoid layoffs.

At the same time, Mr. Mumtaz said, he started drawing new customers, including those who used to frequent nearby independent restaurants and bars that still remained closed. Mr. Mumtaz said that his Pizza Hut same-store sales were up 18% over last year by the summer, and that business at KFC, Taco Bell and Long John Silver's also rebounded. He has since paid back some of his deferred royalties.

Mr. Mumtaz said he is feeling optimistic: "I'm taking every step carefully."

No Levers to Pull

Turmoil among independent restaurants is cascading down to a swath of suppliers, including many seafood companies and small farmers that mainly serve diners rather than supermarket customers. Every 100 restaurant jobs support 50 more at suppliers such as wholesalers and farmers, according to the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute.

Kate McClendon, co-owner of McClendon's Select organic farms in Arizona, said 95% of her restaurant orders vanished when the state shut down dine-in restaurant service in March. The family-run farm threw together a boxed-produce program to stay afloat, but a lot of the specialty greens they grow for chefs didn't translate into demand from home cooks. She said the farm has recouped fewer than 60 of its 90 regular restaurant customers, and that orders are being placed roughly half as often.

"Independent farms rely on independent restaurants. Big chains don't buy from local farms," Ms. McClendon said.

Many independent restaurants are suffering partly because they tend to have smaller physical footprints, especially in higher-cost big cities. Camilla Marcus closed West-bourne cafe in Manhattan's SoHo neighborhood in September after her landlord declined to offer a break on her rent. West-bourne had no patio, and Ms. Marcus said the return of indoor dining at 25% capacity wouldn't work at the communal tables in her 1,000-square-foot dining room.

A woman wearing a mask walks past a "For Rent" sign on a former restaurant's window. (Photo by Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images)

GET FOX BUSINESS ON THE GO BY CLICKING HERE

"With just one location, there are just no levers to pull," said Ms. Marcus, a co-founder of the Independent Restaurant Coalition, which is lobbying Congress to pass a stimulus package backed by House Democrats that would allot $120 billion for the sector.

Nick Kokonas, co-owner of the Chicago-based Alinea Group of four high-end restaurants, has relied on a rotating to-go menu to keep his operations afloat. Two of his restaurants made money last month, one broke even and one lost $100,000, he said. He is considering closing some of them for the winter to preserve cash.

"We'll be open through December. Then we don't know," Mr. Kokonas said.

Robert St. John, an owner of restaurants and bars in Hattiesburg, Miss., closed his restaurants in March when the state ended dine-in service, and filed a mass unemployment claim for his 300 employees.

Banks restructured some of his loans, Mr. St. John said, and he received a PPP loan of roughly $600,000. But with sales down about 70% across the six restaurants, he said, he couldn't justify bringing back many employees. An attempt at socially distanced dining at his Italian restaurant ended due to insufficient demand.

"There was no real excitement or fever about us reopening," Mr. St. John said.

By the summer, Mr. St. John decided to close his flagship Purple Parrot Café, a destination eatery for the area that boasted $4,000 bottles of wine, after 32 years. He said he knows couples that celebrated prom together at Purple Parrot and now have been together for decades.

He has also since closed a cocktail bar and a high-end doughnut shop, as business from Hattiesburg's University of Southern Mississippi dried up with the school's shift to virtual learning. Mr. St. John, who described himself as an optimist to a fault, is applying for a $500,000 small-business loan to build a new restaurant with a big patio where he can serve people outdoors.

"It's scary, I'll tell you," he said. "I would refuse to think that I would have to shut down more."