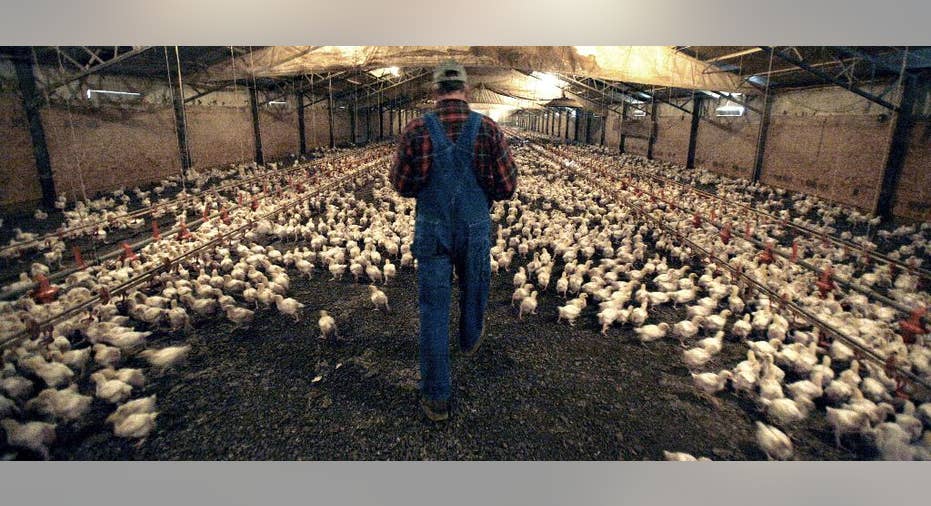

Chicken farmers say processors treat them like servants

DES MOINES, Iowa – Former chicken farmers in five states have filed a federal lawsuit accusing a handful of giant poultry processing companies that dominate the industry of treating farmers who raise the chickens like indentured servants and colluding to fix prices paid to them.

The farmers located in Alabama, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma and Texas allege that the contract grower system created by Tyson Foods, Pilgrim's Pride, Perdue Farms, Koch Foods, and Sanderson Farms pushed them deep into debt to build and maintain chicken barns to meet company demands.

They say the companies colluded to fix farmer compensation at low levels to boost corporate profits, making it difficult for the farmers to survive financially. They are seeking class action status for the suit filed in federal court in Muskogee, Oklahoma.

The scheme keeps farmers in a state of indebted servitude "living like modern-day sharecroppers on the ragged edge of bankruptcy," the lawsuit filed on Jan. 27 says, quoting from the 2014 Christopher Leonard book "The Meat Racket: The Secret Takeover of America's Food Business."

Under the contract system, farmers provide the barns and labor to raise the chickens and the company provides chicks, feed and expertise to raise birds to slaughter weight.

The companies named haven't yet responded to the lawsuit in court, but one denied the allegations.

"We want our contract farmers to succeed and don't consult competitors about how our farmers are paid. These are false claims," said Gary Michelson, a spokesman for Tyson.

He said the average contract farmer has been raising chickens for the company for 15 years and the compensation paid is clearly outlined in contracts farmers voluntarily sign, but declined to give more details.

The five farmers who filed the lawsuit have quit raising chickens, and some of them say they are tens of thousands of dollars in debt.

The farmers and their attorney declined to comment beyond the details in the lawsuit. But other chicken farmers who could be represented if the case is certified as class-action, spoke of going deep into debt to build modern chicken barns as long as two football fields with the promise of generous profit.

"The farmers put their homes and their farms in hock to borrow the money to build these things. Once they do, the companies have control over them period," said Mike Weaver, 62, of Fort Seybert, West Virginia, who's is in his 16th year of raising chickens for Pilgrim's Pride. "We're hoping to bring about a change in this system. It has to be done. If not, the American family farmer is going to disappear."

While Weaver said he does not have debt, he said that he knows farmers who have lost their farms.

The lawsuit asks a federal judge to find the contractual scheme and the alleged agreements to fix payments to chicken growers unlawful under two sections of federal law, the Sherman Antitrust Act and the Packers and Stockyards Act. Farmers are seeking damages, costs and interest.

The farmers said in the lawsuit their net incomes ranged between $12,000 and year and $40,000 a year despite working 12 to 16 hours a day every day of the year.

"Meanwhile, integrators like Pilgrim's Pride and Tyson rake in more than $1 billion and $3.9 billion a year, respectively, in profits," they said.

The lawsuit said it expects tens of thousands of farmers to qualify as members of the class.

The farmers are Haff Poultry in Oklahoma; Craig Watts, North Carolina; Johnny Upchurch, Alabama; Johnathan Walters, Mississippi and Brad Carr of Texas.

The National Chicken Council, an industry trade group representing the companies, said with any contracting situation there will always be a disgruntled minority.

"The way that the system is set up, it's a performance-based and incentive system that rewards those farmers who invest who put in the most work and raise the healthiest birds," said Tom Super, the group's spokesman.

He said the contract system has worked for nearly six decades because it benefits companies and farmers.

Per capita chicken consumption has grown 9 percent from 2010 and is expected to reach 91.7 pounds per person this year, according to the National Chicken Council. U.S. consumers spend more than $90 billion a year on chicken, making it the number one meat protein consumed.

On Tuesday, Tyson Foods said it has been subpoenaed by the Securities and Exchange Commission for an investigation it believes is tied to allegations that it violated antitrust laws, issues raised in two other lawsuits. Both of those lawsuits related to alleged price fixing and collusion.

Some issues brought up by the farmers' lawsuit were addressed by USDA in the last month of the Barack Obama administration but the new administration of President Donald Trump delayed implementation of the rules until March or April. The rules would make it easier for farmers to sue and protect the legal rights of growers.

The rules could "open the floodgates to frivolous lawsuits," said Super, the industry trade group representative.