Evergrande restructuring is a warning to China’s other creditors

Offshore creditors who lent property developer billions are discovering they have little recourse

China anticipates being isolated from the global order: Brig. Gen. Rob Spalding

Retired U.S. Air Force Brig. Gen. Rob Spalding reacts to China issuing a warning against global rate hikes on 'Cavuto: Coast to Coast.'

China Evergrande has finally laid out a debt-restructuring plan for its offshore creditors. The pain for its long-suffering debt investors, however, isn’t over yet.

That also gives a warning to owners of other offshore property debt. Many investors piled into those bonds on the assumption that Beijing would never allow a truly widespread property bust because of the fraught politics of homeownership in China. That assumption proved wrong, and now they are likely to pay a steep price.

Evergrande on Wednesday unveiled a plan to restructure $19 billion of its offshore debt. Creditors will be given two options: swap their bonds into new notes with a tenor of 10 to 12 years or accept a combination of new five- to nine-year bonds and securities that could convert into shares of Evergrande and its two Hong Kong-listed units, including its property management unit.

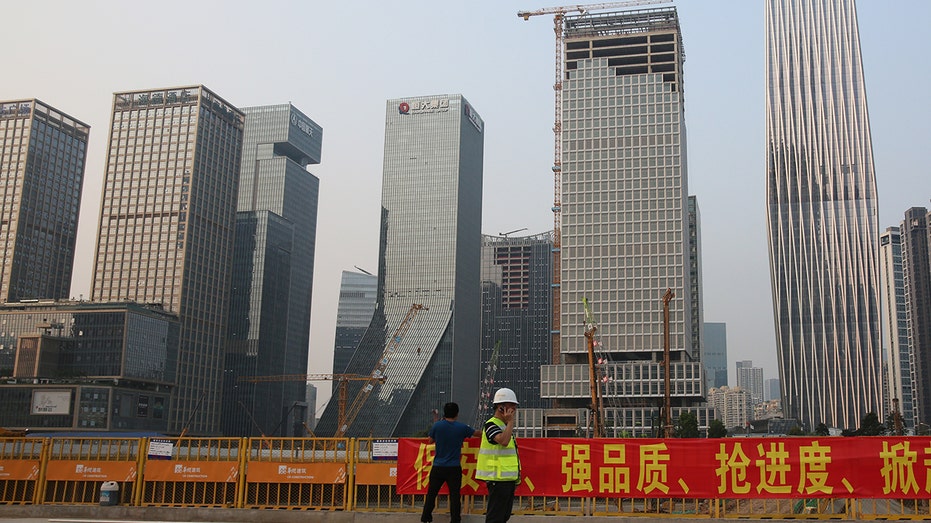

A picture taken on Sep. 29, 2021 shows the headquarters building of Chinese developer Evergrande Group(C) in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China. The group is in financial crisis. (The Yomiuri Shimbun)

Neither option is particularly attractive. Evergrande can choose to pay the coupons on the longer-dated bonds with more bonds. It can choose to do so partly for the bonds being offered for the other option, too. The equity-linked securities might offer better value. But that is also highly uncertain.

CHINA'S EVERGRANDE: WHAT TO KNOW

Its property service unit should in theory receive relatively stable revenue from managing apartment complexes—but banks seized about $2 billion of deposits from the unit last year after Evergrande itself improperly used them as a guarantee to borrow more money.

And Evergrande’s listed electric-vehicle unit is essentially just another property developer with a nominal EV business—it has delivered only some 900 cars so far. The EV company warned Wednesday that it may stop production if it cannot secure additional financing of at least $4.3 billion.

Residents pass near the headquarters for Evergrande in Shenzhen in southern China, Thursday, Sept. 23, 2021. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan / AP Newsroom)

Trading in Evergrande’s Hong Kong-listed shares and both other listed units have been suspended for about a year, after they failed to file financial reports on time.

While China’s real-estate market is starting to recover, Evergrande itself is a different story: It said it needs additional funding of $37 billion to $44 billion during the next three years, and all free cash flow generated will be needed to repay new debt and finish already sold apartments.

CHINA EVERGRANDE’S MANAGED RESTRUCTURING IS UNDER WAY; STOCKS AND BONDS SINK

But creditors probably won’t have a better option. Stakes in the two listed companies are already some of the more valuable assets that Evergrande owns outside mainland China. The likely recovery values of existing offshore bonds are only 2% to 9% of principal in the case of liquidation, according to a Deloitte analysis commissioned by the company. Such a low recovery rate isn’t unexpected. Evergrande’s dollar-denominated bonds have been trading below 10 cents on the dollar for quite a while.

Evergrande offshore creditors will have the option to receive a combination of new five- to nine-year bonds and securities that could convert into shares of Evergrande and its two Hong Kong-listed units, including its property management unit. Hong K (iStock / iStock)

The fundamental problem is that most of Evergrande’s assets reside in the onshore operating company, which also has its own debts. Offshore creditors were lending to the holding company and would rank lower than those onshore creditors. Evergrande had about 613 billion yuan, the equivalent of $90 billion, of onshore liabilities at the end of 2021 and about 141 billion yuan of offshore liabilities.

And the bad news doesn’t end there.

GET FOX BUSINESS ON THE GO BY CLICKING HERE

Evergrande’s restructuring plan may end up as a template for other beleaguered Chinese developers with lots of offshore debt such as Sunac and Kaisa. As in the case of Evergrande, offshore investors lent to an offshore holding company rather than the onshore entities directly holding assets.

That means that they, too, could end up last in line for repayment. The long-term damage to Chinese companies’ ability to borrow offshore may be substantial—but in the meantime foreign creditors are left holding the bag.