The cost of uncertainty after Brexit

LONDON – Walking the streets of London nearly eight weeks after the Brexit vote, it’s difficult to spot any immediate impact or change in sentiment. Residents and tourists alike continue to clink together sudsy mugs at area pubs, pose in front of Buckingham Palace, and stroll down Fleet Street as they pop in and out of shops and restaurants. The only traces of physical evidence the unprecedented vote even happened are faded get-out-the-vote stamps at a bus stop not far from Big Ben’s clock tower and the Houses of Parliament stationed along the Thames.

The business-as-usual sentiment can be interpreted in one of two ways: The calm before an inevitable economic catastrophe that lurches Great Britain into a recession; or a quiet period preceding years of negotiations between the U.K. and the EU over how to split the two entities with as little economic boat rocking as possible.

The only certainty is the uncertainty that will persist at least in the short to medium term. What happens after that depends on the trade relationship the U.K. hammers out with the EU.

LONDON –

“We don’t know how the U.K.’s preferential access will evolve with respect to the EU, with respect to the EU’s trade partners, and with respect to the rest of the world,” HSBC senior trade economist Doug Lippoldt tells FOXBusiness.com. “So there’s uncertainty, and that can be costly in the short term because businesses do not have the full set of information they normally would have to make investment decisions or long-term trade decisions.”

Indeed, early data collected during the first half of July – just weeks after the June 23 referendum – showed businesses became more worried about the nation’s economic future. The U.K.’s service sector, as measured by Markit/CIPS data, saw a drop in business activity as output and new business declined for the first time in three-and-a-half years, putting the index below the 50 mark separating expansion from contraction. What’s more, the nation’s factory sector also slipped into contraction territory in July to its lowest level since early 2013.

By August, both manufacturing and services experienced a rebound from the initial shock – a return to business as usual. Manufacturing rose to a ten-month high as work that was postponed restarted, while services saw its biggest month-on-month gain in the survey’s 20-year history as the gauge returned to growth but remained weak by historical standards, according to the survey’s sponsor.

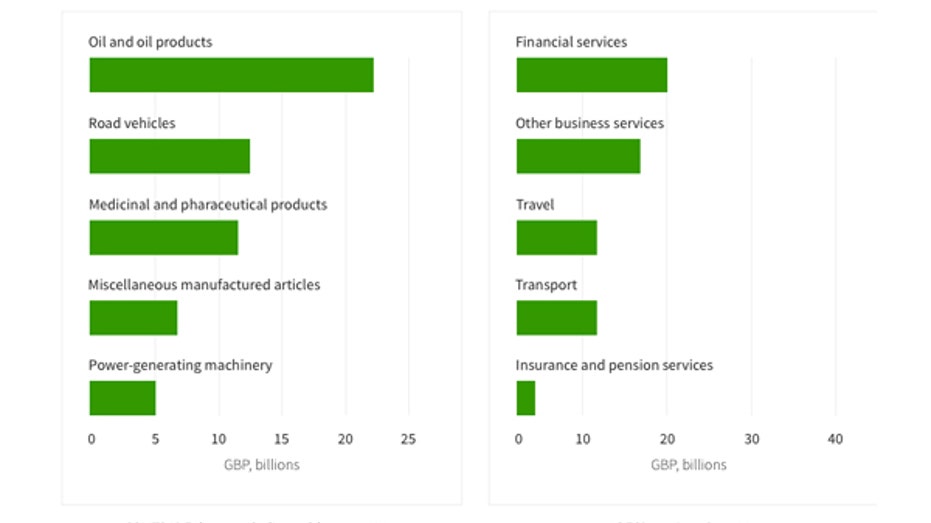

While Britain still sees investment in the movement of physical goods into and out of its borders, the services sector accounts for nearly 80% of the U.K.’s overall gross domestic product. A big question post-Brexit vote is what happens to Britain’s financial services industry, which operates in part through a number of global firms like Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS), KPMG, Citigroup (NYSE:C), Bank of America (NYSE:BAC), and a host of others, with headquarters in the U.K., exporting their services all around the world.

“London is the No. 1 financial center of the world. Businesses [in the EU] have access to financial services that they couldn’t otherwise get in such a cost-competitive fashion. There will be stakeholders on the [European] continent that wish to maintain access to the U.K. services market. Likewise, the U.K. runs a merchandise trade deficit with the continent, so there are sellers on the continent that have a keen interest in maintaining access to the U.K. market,” Lippoldt explained.

In essence, stakeholders on both sides of the English Channel will want to see preserved the openness of the current market – referred to as the single-market. The problem is no one is certain to what degree that might happen. Lippoldt suspects the benefits both sides enjoy will be enough to guide future talks and tamp down any lingering anger over the outcome of the vote.

Like many questions surrounding the post-Brexit vote world in which the U.K. finds itself, exactly how a future trade deal is negotiated with its EU counterparts, or what the top priorities for Prime Minister Theresa May include, are unknown. The country has yet to trigger Article 50: A provision within the Lisbon Treaty – the constitutional basis for the European Union – that officially begins the process of the U.K. unwinding itself from the EU.

May has said she does not plan to invoke Article 50 this year, but Miriam Gonzalez, a partner at Dechert who specializes in international trade and government regulation having acted as the lead EU negotiator for the World Trade Organization telecoms agreements, said May and her cohorts need to swiftly outline a roadmap for how they’d like to see negotiations begin.

“What is very urgent is that the government gives at least some general indication of the kind of model they would like to get...It is very difficult for companies to navigate because there are a lot of possibilities and at some point, they need to continue making investment decisions…everything we hear from business is they are concerned about the lack of legal certainty now,” Gonzalez said.

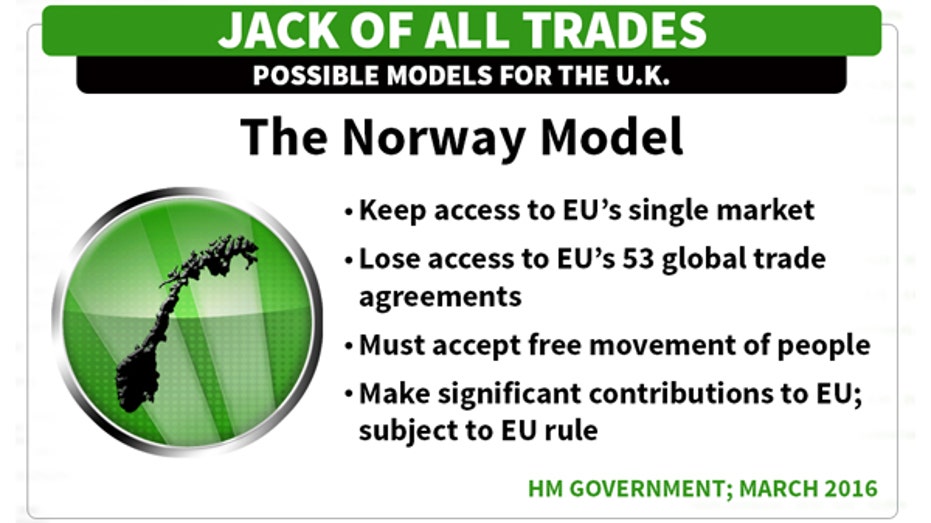

Indeed, as negotiations play out and the U.K. begins to understand exactly the mechanics of how a separation from the EU would take place, trade negotiations with other nations would not be far behind. The U.K. could adopt a range of models, including one like Norway, which would essentially allow it access to the European Economic Area as it would accept a majority of EU laws. The hitch with that plan is in order to gain access to the single market, the U.K. would likely have to accept the free movement of people, or visa-free travel by EU citizens. It’s a requirement that motivated many British citizens to cast their vote in favor of Brexit back in June.

At issue for many U.K. citizens is a struggle for the EU to contain a migrant crisis in the region caused by a flood of immigrants and refugees, largely from Syria, Afghanistan, Kosovo, and Nigeria. The mass migration into the region is the largest since 1945 and has worried many EU residents concerned about the growing threat of global terrorism and an open-border policy that prevents a rigorous checks-and-balance system for immigration.

“The key question is whether the EU is willing to compromise at all on the free movement of people. If the EU as a whole decides that its approach to that needs to change because of the migration crisis and other political pressures in other countries, and they feel that whole concept needs to be adjusted, that would make it easier because then it won’t be just giving special treatment to the U.K.,” PricewaterhouseCoopers chief economist John Hawksworth explained.

As evidenced by the Brexit referendum’s result, the EU isn’t keen to budge on the free-movement issue. Therefore, if the U.K. wants access to the single market, it more than likely must also accept an open-border policy.

“Clearly it’s been a sticking point for negotiations. Before the referendum, basically [former Prime Minister] David Cameron was not able to get any meaningful concessions on that point. It will remain a tricky area,” Hawksworth predicted, adding another tick to the uncertainty column for British citizens and corporations alike.

In a statement last week, May said Britain would seek a unique relationship with the EU involving both controls on immigration and a favorable trade deal.

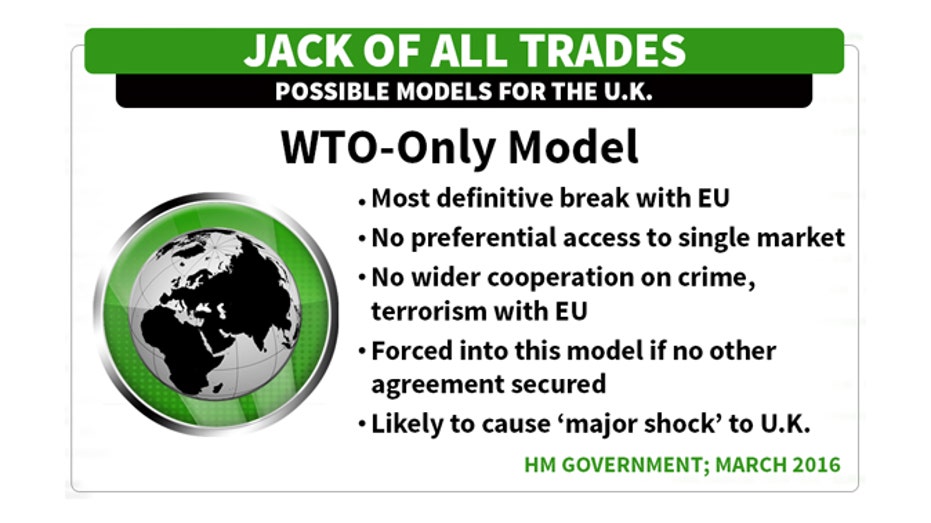

The focus then, for the U.K. becomes working out an amicable solution on trade with not just the EU, but other nations of the world. The complexity surrounding the legal logistical puzzle can almost be boiled down to the existential question of: Which came first – the chicken or the egg. For the U.K., the question becomes where can the nation trade, and under what rules?

“The U.K. does not really have the legal basis to [negotiate agreements] because they can’t sign bilateral agreements until they’ve stopped being a member of the European Union. I hope that if everything is kept on friendly terms, we can agree that we can start some preliminary discussions with third countries so this doesn’t lead to a 15-year process,” Gonzales said.

This is the second piece in a three-part series exploring how Brexit will impact the future of the United Kingdom’s overall economy, and its ability to trade with the rest of the world.