Cato's Chris Edwards: What Warren and Sanders get wrong about wealth inequality (and capitalism)

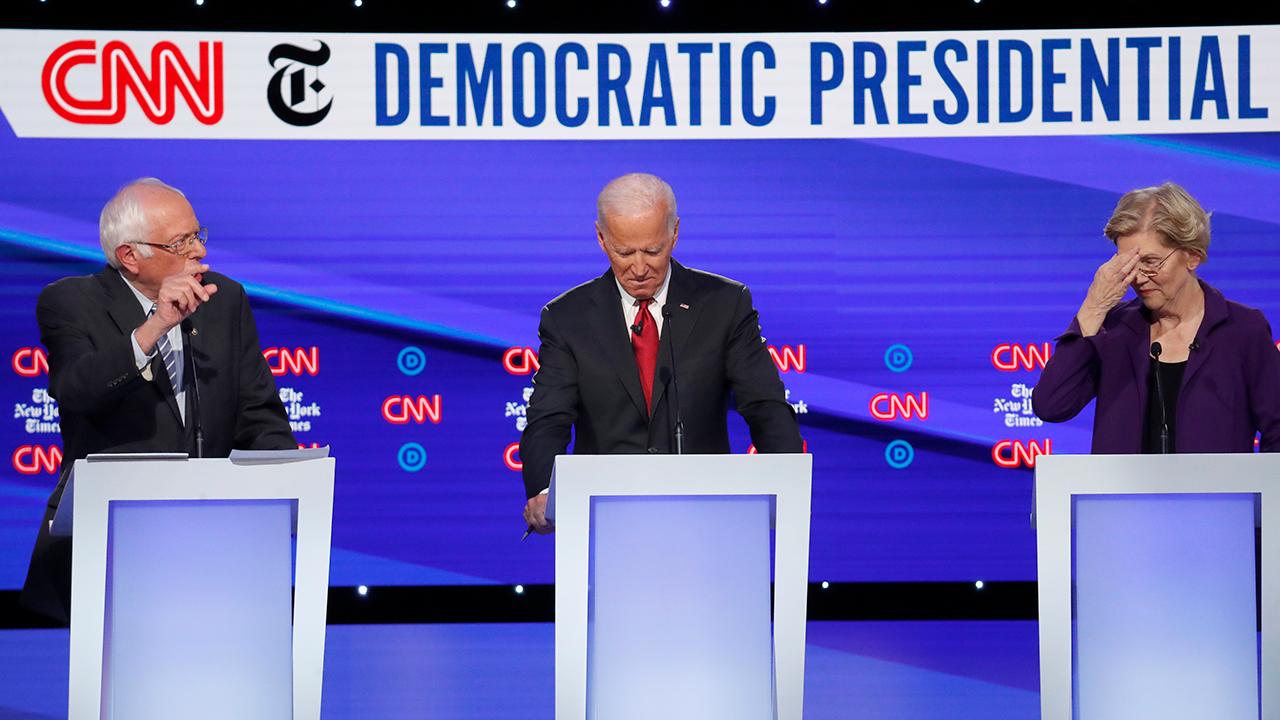

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., are fueling their presidential campaigns by generating anger toward the wealthy.

Warren is blasting America’s “extreme concentration of wealth,” while Sanders is condemning wealth inequality as “outrageous” and “grotesque.” Both want to hammer the rich with a new annual wealth tax.

From left, Democratic presidential candidates, Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, D-Hawaii, businessman Tom Steyer, Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., Sen. Kamala Harris, D-Calif., Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., former Vice President Joe Biden, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass.,

Moderate candidates on the debate stage Tuesday night were right to call Warren’s and Sanders’ tax and spending plans unrealistic. The almost twin leftists are also oblivious that wealth inequality may reflect starkly different economic causes. As such, their broad-brush denunciations of wealth are a useless guide to public policy.

Consider three different causes of wealth inequality: cronyism, crowding out and capitalism.

Cronyism

Cronyism means businesses gaining subsidies and narrow regulatory benefits at public expense. Farm subsidies, for example, cost taxpayers and go to the wealthiest farmers. Cronyism increases inequality and undermines the economy, and so Warren and Sanders are right to complain about it.

Crowding out

Crowding out refers to government social programs displacing private wealth-building. Social Security, for example, reduces incentives for private retirement saving, and the program’s heavy payroll taxes reduce the ability to save.

Crowding out mainly affects the non-wealthy, so it increases wealth inequality. Warren and Sanders want to expand social programs, but that would make this problem worse.

Capitalism

The two candidates are also wrong about capitalism. The explosion of new technologies in recent decades has made many entrepreneurs rich. The Forbes list of the wealthiest Americans includes many people such as Robert Pera, founder of Ubiquiti Networks, which brings low-cost internet to underserved and rural areas around the globe. Such billionaires help uplift the poor, so punishing them with a wealth tax — as Warren and Sanders propose — makes no sense.

The three causes of wealth inequality are evident in cross-country comparisons. Sanders complains that the United States has more wealth inequality “than any other major country on earth.” It is true that our Gini coefficient is fairly high at 85, according to Credit Suisse. Ginis range from 0 to 100, with higher numbers meaning more wealth inequality.

Yet such metrics tell us nothing without knowing the causes. America’s wealth inequality is partly caused by cronyism and crowding out, but the main cause is our dynamic economy. Entrepreneurs are gaining wealth by innovating, and that raises overall growth and living standards.

Warren and Sanders want more equality, but they would not want to live in most of the countries that have it, such as Ethiopia, Burma and Pakistan. Those countries have low Ginis of 61, 58 and 65, respectively, indicating a high degree of equality — but it is an equality of widespread poverty.

Some countries have higher wealth inequality than America, including Egypt (91), Kazakhstan (95), Russia (88) and Ukraine (96). What do those countries have in common? High levels of cronyism or corruption, according to Transparency International. In these countries, cronyism is a cause of both high wealth inequality and the generally low living standards.

Another group of countries has low corruption yet high wealth inequality, including Sweden (87), Denmark (84) and Norway (79). The problem, Credit Suisse notes, is crowding out: “strong social security programs . . . can greatly reduce the need for personal financial assets . . . This is one explanation for the high level of wealth inequality we identify in Denmark, Norway and Sweden: the top groups continue to accumulate for business and investment purposes, while the middle and lower classes have a less pressing need for personal saving than in many other countries.”

Consider a different economic metric that we can all agree on. The United Nation’s Human Development Index measures each country’s income levels, life expectancies and educational opportunities. Across 167 countries, the index shows modest positive correlation with wealth inequality as measured by the Gini coefficients — the opposite of what Sanders or Warren might think. Countries with open market economies — such as the United States — provide opportunities for entrepreneurs to become wealthy, and that in turn generates growth and raises overall human development or living standards.

China’s wealth inequality has risen in recent decades as many entrepreneurs have built fortunes. At the same time, general living standards have soared: since 1990, China’s real GDP per capita has expanded 10-fold and the share of its population living in severe poverty has plunged from 47 percent to just 1 percent. Whatever wealth inequality statistics may show, vast numbers of people are living much better lives in China, and that is the economic fact that matters.

GET FOX BUSINESS ON THE GO BY CLICKING HERE

Given these realities, why do Democratic candidates gripe endlessly about wealth inequality? After all, only a tiny share of the public thinks that the gap between rich and poor is a top concern. The answer seems to be that Warren, Sanders, and other leftists are trying to convince their followers that the economy is a zero-sum game — that the wealthy only gain at everyone else’s expense.

Sanders, for example, claims that “there has been a massive shift of wealth from the middle class to the top one percent.” But such shifting is only true for wealth made through cronyism, not wealth from market-based capitalism that dominates the American economy.

Sanders and Warren would be more constructive if they proposed detailed plans to end “crony-ist” programs such as farm subsidies. They could also further their goal of reducing wealth inequality by supporting a transition to savings-based social programs so that the non-wealthy can build assets.

Until leftist politicians get on board with those sorts of real solutions, their complaints about inequality are no more than empty rhetoric and spiteful egalitarianism.

Chris Edwards is director of tax policy at the Cato Institute and editor of www.DownsizingGovernment.org.