Death and taxes frame estate tax debate

The estate tax affects a very small — and very wealthy — number of Americans.

Only the estates of about 2 out of every 1,000 Americans who die face this tax right now.

Easing or repealing the tax — currently under consideration in Washington — would lower federal revenue and potentially generate a windfall for some ultra-wealthy families.

The estate tax accounts for around 1 percent of the federal government's total revenue. And it symbolizes a major issue at the heart of the tax overhaul debate: whether the Republican proposals unfairly provide more benefits to the wealthy over low- and middle-income Americans.

Here's what you should know:

What Is It?

When someone dies, the estate they leave their heirs is subject to federal taxes when its value exceeds a certain threshold. That threshold, or exemption as it is known, has risen dramatically in recent years and at last measure was nearly $5.5 million for individuals or $11 million for couples.

The IRS measures the estate by the fair value of all assets — cash, stock, real estate, business interests and more — at the time it is handed down. But the estate is only taxed at the value above the exemption level.

So that first $5.5 million, or $11 million? It's tax free. Anything beyond that is taxed at the top level of 40 percent.

But the Tax Policy Center says the effective rate is much lower, because of that sizeable upfront exemption and other provisions that allow the wealthy to protect their money from taxes.

Who Pays It

Only the wealthiest 0.2 percent of estates owed any estate tax at last count, according to IRS data and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

It used to be more estates faced the tax, but the exemption has climbed — jumping from $600,000 20 years ago to nearly $5.5 million today — so that now it only applies to the super wealthy.

President Donald Trump — whose has at least $1.4 billion in assets, according to a disclosure with the Office of Government Ethics — is among those who would benefit from an elimination of the rule. Critics have pointed out that other ultra-wealthy members of his cabinet could potentially benefit as well.

The tax rule is criticized as ineffective though, as many wealthy families take steps to lower or avoid their tax burden — including gifting money over time, making charitable donations to shrink the size of their estate or using certain trusts to pass on money with a smaller tax burden. Plus, under existing rules, an estate can be passed to a surviving spouse with no tax penalty.

A long-running argument, still used today, is that the estate tax unduly burdens small businesses and family farms. But the Tax Policy Center estimates that only 80 small business and small farm estates nationwide will face any estate tax in 2017.

The Proposals

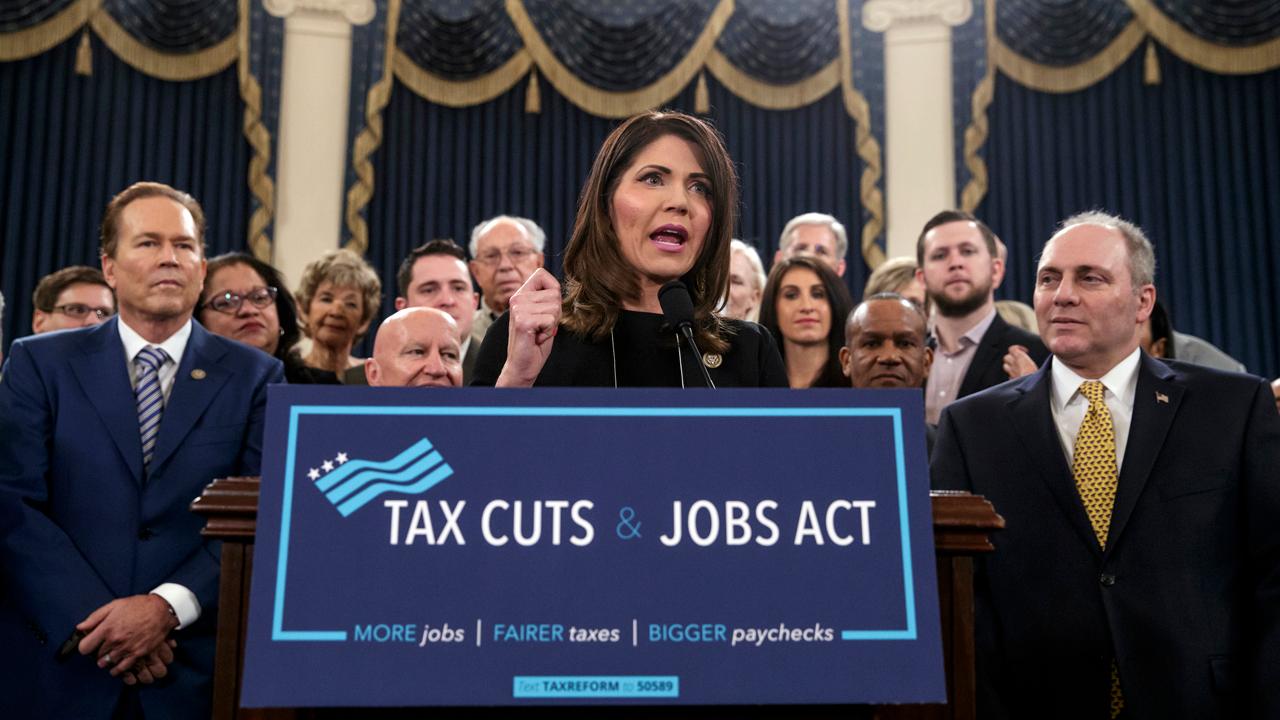

The competing proposals would both tweak the estate tax rules. The house bill initially doubles the exemption to $11 million for individuals and $22 million for couples and repeals the entire tax after 2023. The senate version doubles the exemptions but does not repeal the tax.

Congress is under pressure to act: Trump wants a tax overhaul passed by the end of the year.

Why It Matters

The argument is largely one of tax fairness.

Opponents call the estate tax the "death tax" and say it taxes someone twice — first when they earn the money and again after they die.

House Speaker Paul Ryan, one who has long argued for eliminating the tax, called this "unfair" and said in a recent interview with Fox News that the government shouldn't stop people from passing their life's work to their kids. He and other opponents of the tax say it also inhibits job growth because it kills small businesses.

But proponents and tax experts disagree. They say the tax doesn't affect many businesses and much of the money the wealthy leave behind has never been taxed. That's because the bulk of these massive estates, according to the IRS, are made up of real estate and stocks, which gain in value over time without being taxed.

Left undisturbed, those assets continues to gain in value as they are handed down over the generations. They typically aren't taxed until someone "realizes" its value through a sale, at which time they face capital gains tax.

So the tax is in place to level the playing field and avoid dynastic wealth.

The estate tax will generate about $20 billion in federal revenue this year, according to the Tax Policy Institute. That's not a ton in terms of federal revenue. But it's still a lot of money when looking at a deficit or funding other services.

"It's a stupid tax," said Edward McCaffery, a professor of law, economics and political science at the University of Southern California. "In real comprehensive tax reform there has to be something sensible, including a sensible way to tax the rich."