Dartmouth is the blueprint for NFL success in 2020. Yes, Dartmouth.

Dartmouth eliminated full-contact practices. Injuries plummeted. Success skyrocketed.

Buddy Teevens came up with a crazy idea because he needed one. Dartmouth's football team lost every one of its games in 2008. It won only two in 2009. Teevens knew just two things for certain: his team's injury rate was really high and its success rate was really low.

Teevens's radical plan to turn around an Ivy League football program a decade ago is now the unlikely blueprint for every team in the NFL. Dartmouth eliminated full-contact practices. Injuries plummeted. Success skyrocketed. Rethinking how football teams have practiced for over a century made Dartmouth healthier -- and better.

BODYARMOR SIGNS NFL'S CHRISTIAN MCCAFFREY, 6 OTHERS TO ENDORSEMENT DEALS

Now, the coronavirus pandemic has forced Bill Belichick, Andy Reid and every NFL coach to follow the lead of Buddy Teevens. This season's player safety protocols ban padded practices with full contact in NFL camps until Aug. 17, three weeks after players first report.

It's a contentious restriction for the same reason Dartmouth's strategy was such an outlier in 2010 and still is today: For as long as players have run with an oblong-shaped ball toward a patch of grass called an end zone, coaches have believed the most effective way to prepare players is by practicing it with the same physicality as in a game. Anything less has been rebuked by purists as sacrificing the quality of the sport in the name of safety.

Teevens looked at the problem differently than all of his peers. His team was both bad and hurt. At the same moment when there was a growing national conversation about football's long-term health risks, he wondered if his team could be less bad by being less hurt.

So after winning two games in as many years, he marched into a meeting with this staff one day with an edict: Dartmouth was going to phase out live contact from all of its practices. The players weren't going to train for games anymore by tackling and mauling one another. It was such a deviation from football orthodoxy that everyone in the room looked at him like he had goalposts for arms.

BODYARMOR HEATS UP SPORTS DRINK WARS, EYES GATORADE'S TOP SPOT

"Guys thought it was a joke. They were just waiting for the punchline," says Teevens, who is still Dartmouth's coach. "They were looking at me like: What are you thinking?"

Teevens was actually thinking about the past advice he had received from two guys who knew one or two things about winning football games: Bill Walsh and Steve Spurrier.

After playing quarterback for Dartmouth in the '70s, Teevens's coaching odyssey included stints with two of the greatest minds to ever draw plays on a chalkboard. For three seasons, he was an assistant under Spurrier at Florida. The next three years, he was the coach at Stanford, where Walsh returned as an administrator after once serving as the school's coach.

These two coaches are hailed for their progressive offenses, but Teevens says they were even more progressive when it came to protecting their players. They both instilled in him the idea that little was more important than getting their team to game day in tip-top shape. Unlike other coaches, they didn't take pride in having their players batter each other every day.

"Why would you beat the crap out of our own team and players?" Spurrier says. "I used to tell people: When the army's preparing for battle, they don't use live bullets against each other. So why use live collisions when we get ready for opponents?"

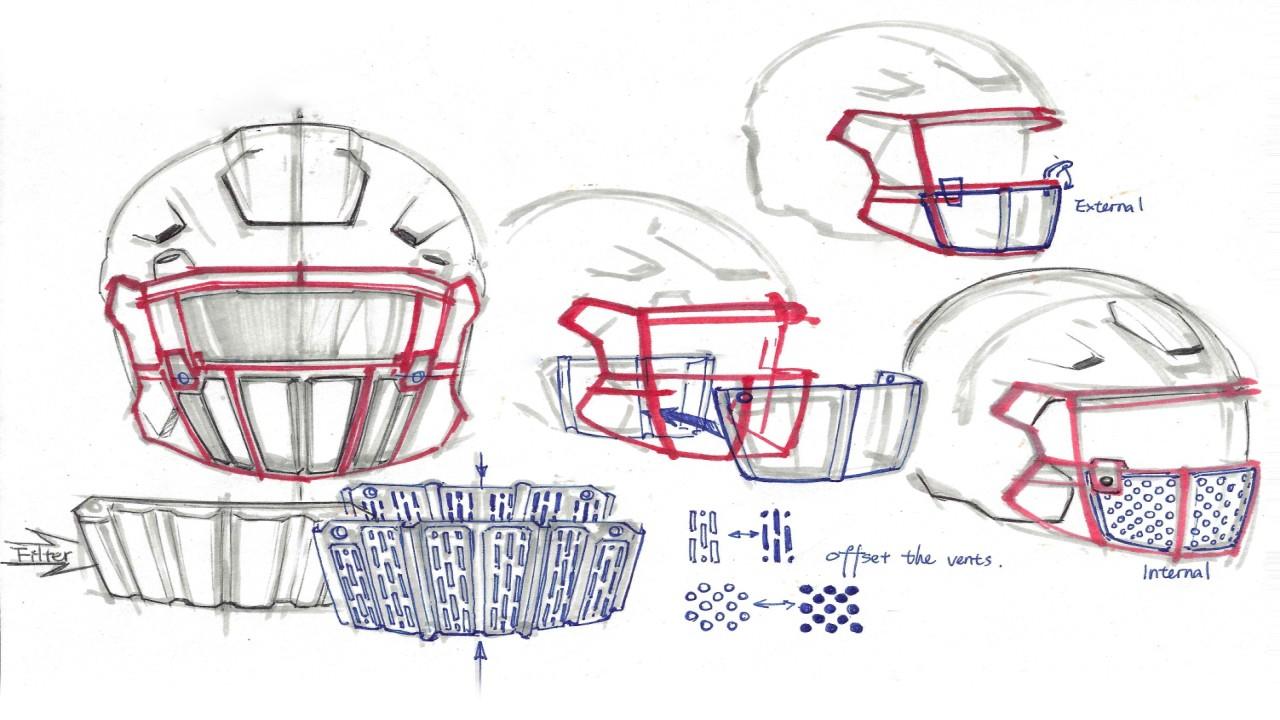

Teevens took that logic to the next level. He had no idea if it would be effective. "If it didn't work, I'm fired and unemployed right now," he says. But he thought he could build an entire system around it. The coaches broke down film to study the most effective tackles. They later brought in robotic tackling dummies so players had mobile targets to practice against. They were still training for the violence inherent to football -- just not against their own teammates.

GET FOX BUSINESS ON THE GO BY CLICKING HERE

Players say there was an initial skepticism. They had practiced a certain way in high school. Other college teams did too. So did the best of the best in the NFL. When Teevens walked into players' homes for recruiting visits, they had the same reaction as his coaching staff. "I wasn't a full-on believer at the beginning," said Will McNamara, a Dartmouth linebacker from 2012 to 2015.

But players like Will McNamara became believers when they actually tried it. They felt fresher, and they played better. Concussions went down. Missed tackles went down. And the most important statistic went up: wins. From 2005 to 2009 under Teevens, Dartmouth's record was 9-41. Over the next 10 years, it went 70-30 with two Ivy League titles.

"The proof is on the scoreboard," said Bronson Green, a former Big Green captain and linebacker. "This may be the next evolution of where the game should be."

When this experiment proved so successful, this school in football's hinterlands became the curiosity of the football world. The Ivy League eliminated full-contact practices during the season in 2016. Teevens's phone kept ringing with scouts, coaches and executives eager to hear how it worked.

Those executives have included NFL chief medical officer Dr. Allen Sills, executive vice president of football operations Troy Vincent -- and their boss. Two years ago, Teevens was conducting a spring practice and noticed his players were awfully distracted. They couldn't stop staring at the person peppering their coach with questions. Which is when Teevens asked Roger Goodell to give a speech to the team so they could get on with their practice. The NFL commissioner was so intrigued he bought some of the same tackling dummies Dartmouth uses for Bronxville High School in the New York suburb where he lives.

But the NFL wasn't anywhere near making its practice look like Dartmouth's. Then a novel virus brought the country's richest sports league, and the school that helped inspire "Animal House," closer than anyone could have imagined.

When the NFL and its union began bargaining over how to return during a pandemic, they wanted protocols to mitigate the spread of the virus and a plan to prevent an increase in injuries. The resulting agreement eliminated preseason games and said practices would not include full pads or contact for the first three weeks of training camp.

It's a jarring shift to football normalcy. But one former NFL and college coach says it's hogwash if people say the techniques that worked at Dartmouth won't work in the NFL.

"I don't agree with that at all," Spurrier says. He added: "When you have injuries in practice, that's really stupid."

Write to Andrew Beaton at andrew.beaton@wsj.com