Dangerous drones: Why flying robots are weapons and how to stop them

It may be time to look up.

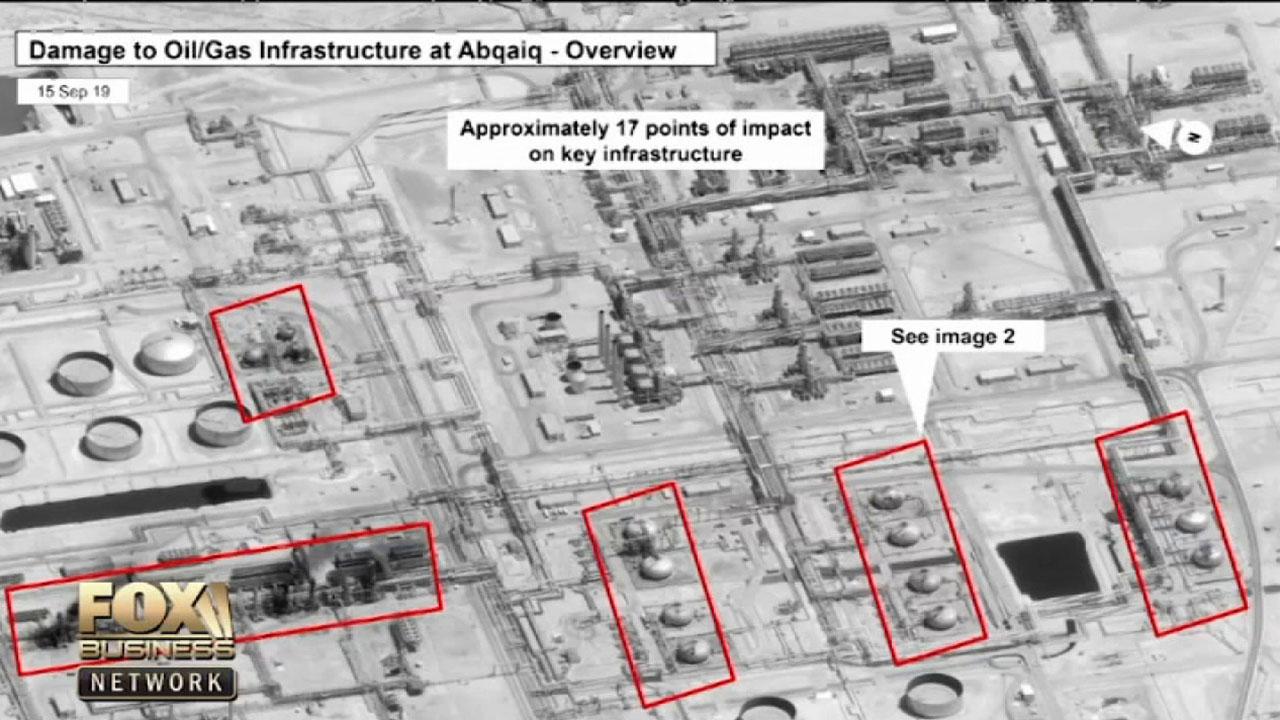

Last week, a series of drone attacks were launched on one of the world’s largest oil processing facilities in Saudi Arabia, knocking out half its production and sparking toxic fires that burned for days.

It’s not out of the question that a similar attack could be carried out in a populated U.S. city.

“It’s not only possible, it’s probable,” Brent Brown, chairman and chief executive officer of investigative agency Chesley Brown International, told Fox Business. “I would venture to guess this is already being thought out. And it's quite a concern to security industries.”

Already, unmanned vehicles have been causing havoc at airports. Pilots at Newark Liberty International have reported spotting drones before takeoff, prompting the delay of 170 outgoing flights early this year and the diversion of nine incoming flights to other hubs.

A drone flew over Michigan Stadium this month during a football game, leaving two people in police custody. One in July hovered above a fire in Arizona, halting critical recovery operations. And another, strapped with fireworks, was found on a rooftop in downtown Los Angeles days earlier, causing authorities to close off an entire street.

The Federal Aviation Administration said spottings have “increased dramatically over the past two years” and that they now “receive more than 100 such reports each month.”

The agency explained on its website that unauthorized drone use, especially around airplanes, helicopters, airports and other no-fly zones is “dangerous and illegal.” Unlawful operators “may be subject to stiff fines and criminal charges, including possible jail time.”

But aviation and security experts are still concerned.

While the FAA requires flyers to register their devices, bad actors can still make modifications outside of agency standards, Daniel R. Young, founder and chief information officer at security agency Circadian Risk, told Fox Business. “These drones can fire guns and can carry chemical weapons, biological weapons and explosives.”

According to Circadian, drones used in agriculture can fly long distances, and have carrying capacities up to 22 pounds, which is a reason for worry since the Federal Emergency Management Agency says a pipe bomb is generally in the range of 5 pounds.

“With this type of payload delivery method available, it is a large concern that a group can fly multiple drones into a heavily populated area, such as an open-air stadium or concert, and create a mass-casualty incident,” Circadian pointed out.

“If 100 drones flew into a stadium and detonated, not only will you have blast injuries, but many other people will be injured from trying to escape and trampling others."

This is a possibility that “people should take seriously,” Young said.

Plus, there’s the potential drones could be used as spies: “Just imagine you're doing [research and development] and you have a prototype of a specific vehicle,” Young said. “You have a drone flying over your property taking photos and releasing those photos to car magazines. How detrimental could that be to your brand and what you’re working on?”

Some companies are developing ways to counter bad drones.

One method: other drones programmed to attack malicious devices. Another: jammers that disrupt the signal from the original pilot and take over the device completely. There are also net cannons and rubber bullets that can disarm bad actors. But perhaps most surprisingly: birds. Eagles and hawks are being trained to take out drones that pose a threat.

With every solution, however, there are caveats. If a drone is equipped with a gun, a bird won’t do much. Net cannons can have limited firing ranges. And even if a drone is captured or shot down, when it falls from the sky, “where is it going to go?” Brown said.

Then there’s the challenge of determining a drone’s intent before it’s acted out.

Brown thinks the answer lies in enforcement of already existing rules, like no-fly zones. Though, that may not “necessarily stop an attack on a public event or a concert.”

That's "after the fact-type stuff, and frankly, as we saw on 9/11 … it was very much against the law for the terrorists to take control of the cockpits and fly planes into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon,” he said. “But that didn't stop them from doing it.

“If you're going to weaponize something, you're not going to follow the law," he added. "So it's more of how are we going to handle it when these things are spotted? How do you contain them?”

Officials are still grappling with ways to do that. Meanwhile, the money behind drones keeps growing.

Total drone unit sales hit 2.2 million worldwide in 2016, according to research firm Gartner, and revenue surged a whopping 36 percent. Some reports forecast drone sales could surpass $12 billion in 2021, compared to just $8.5 billion in 2016.

Of course, the picture isn’t all grim. There are good uses for drones happening all the time, like dropping life preservers to people drowning at sea, surveying traffic accidents before officials make it to the scene and delivering medication to sick people.

There are huge benefits to drones, Brown said. “But, like with anything else, people are going to figure out how to make it bad. We just have to figure out a counter-response.”