China-India friction goes way beyond borders

A tense border standoff between China and India has magnified friction over trade and security between the two nations days before their leaders meet face to face.

In India, the strife on a remote Himalayan plateau has fanned hostility toward Chinese companies and calls for economic retaliation against China, whose soaring exports to India have already invited criticisms of unfair trade.

The scenario echoes Chinese disputes with other nations, including the U.S., as China's trade relationships get caught up in other bilateral strains.

President Donald Trump has launched a trade probe and threatened economic retribution against Beijing, saying it doesn't pressure North Korea enough over its nuclear program. China, meanwhile, has lashed out at South Korea over the installment of a U.S. missile-defense system there, with Chinese consumers spurning the country's autos and other goods.

The Himalayan standoff, which had raised concerns about a potential military conflict, was sparked by China's construction of a road in an area claimed by China and Bhutan, a close Indian ally sandwiched between the two Asian giants. India fears the road will be used for military purposes, reflecting broader territorial ambitions by China that have alarmed New Delhi and pushed it to seek closer defense ties with the U.S. and Japan.

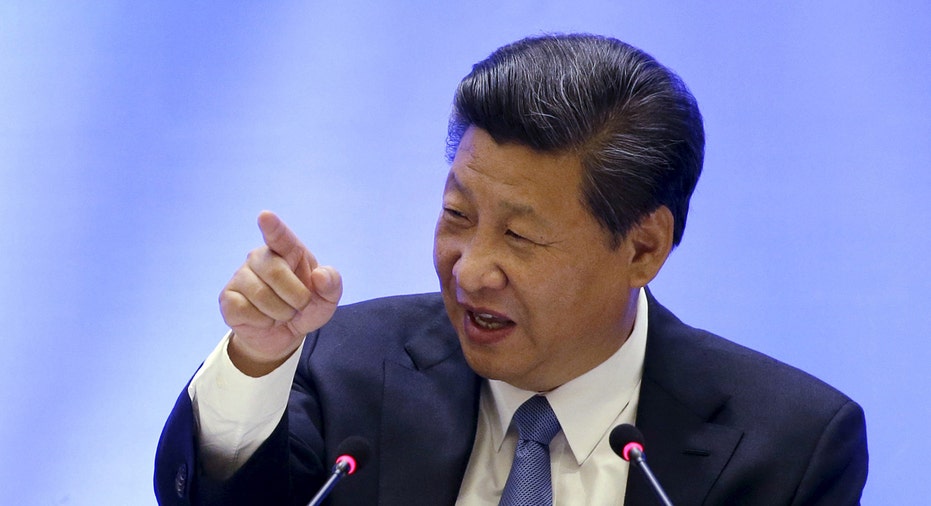

Beijing and New Delhi this week agreed, without disclosing details, to pull back from the brink ahead of a meeting between Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping at a Brics summit in Xiamen, China, that starts Sunday and also includes Brazil, Russia and South Africa.

China and India, the world's most populous nations, are the only Brics countries to have avoided recession in the past year, and they will likely find some common ground at the summit. On Friday, India's Commerce Ministry said the two countries had jointly called on the World Trade Organization to eliminate certain farm subsidies for developed countries like the U.S.

Nonetheless, the border clashes over the past month cloak the relationship in tension.

"This particular standoff is forcing India to rethink its trade strategy, " said Brahma Chellaney, a professor at the Centre for Policy Research in New Delhi. "A lot of Indians during the crisis were asking how India lets China rack up a growing trade surplus while treating India as an enemy."

Exports from China, India's largest trading partner, have quadrupled over the past decade, as China sold rising quantities of electronics, machinery and chemicals. But imports have barely grown as China's slowing economy suppressed its need for natural resources such as copper, cotton and petroleum from India. India also has complained that China is often selling goods below cost.

India's commerce minister discussed trade "in a candid manner" with her Chinese counterpart at an Aug. 1 meeting in Shanghai, India's consulate general there said.

Much as China's untapped market once exerted a pull on the West, India now attracts China. Companies including Chinese smartphone maker Xiaomi Corp. count India as their largest overseas market. Indian consumption will triple to $4 trillion by 2025, Boston Consulting Group estimates, and the country plans a $59 billion infrastructure upgrade. But only about 3% of Chinese exports now go to India.

"The potential could be huge," said Li-Gang Liu, Citi Research economist, of Chinese exports to India. "However, fulfilling this potential remains a challenge, affected not only by tariffs and trade protectionist measures, but also political risks such as border disputes and standoffs."

Chinese-Indian relations have also been strained by the billions of dollars Beijing has invested into infrastructure in Pakistan, India's neighbor and archrival.

India is increasingly wary that China is using trade to advance its strategic aims, said Rajan Menon, a political-science professor at City College in New York. India says one planned route of China's flagship "One Belt, One Road" infrastructure initiative doesn't respect India's territorial integrity.

"India views [the corridor] not so much as an economic plan but as a strategic plan," Mr. Menon said.

Pakistan hopes the corridor will turn it into a trade hub, and give it a second major port besides Karachi, which it fears India could blockade in the event of a war. India is joining Japan on a project that would compete with "One Belt, One Road."

"India sees the so-called China-Pakistan Economic Corridor as strategic encirclement and can't forgive China for its nuclear and missile assistance to Pakistan that has helped offset India's military advantage, " said Rory Medcalf, head of the National Security College at Australian National University.

During the Himalaya confrontation, at the Dolam Plateau, Indian nationalists have protested outside the Chinese Embassy in New Delhi and held events across the country urging boycott of Chinese products. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi played down the backlash on Wednesday in a briefing ahead of the Brics summit and said economic accords would emerge that would help "the rejuvenation of Asia."

"Both China and India are big countries, so it is only natural that some issues will emerge in our relationship," Mr. Wang said. "What's important is that we put these differences in an appropriate place....There is huge potential and space for greater cooperation."

Niharika Mandhana in New Delhi contributed to this article.

By Eva Dou