Labor Secretary: Clarity for 'gig workers' – Proposed rule simplifies definition for contractors, businesses

Freedom from the strictures of a nine-to-five can be especially welcome to parents, caregivers and others

The Department of Labor on Tuesday published a proposed rule defining who’s an “independent contractor.”

Part of what’s notable about this proposed rule is simply that we’re doing it. In the more than 80 years since enactment of the Fair Labor Standards Act, or FLSA, the Department has never adopted a rule defining the term for general industry.

The Supreme Court last spoke to the issue nearly 60 years ago; its most significant pronouncement came just after the Second World War. Since then, employers and workers looking for guidance have had to parse the sometimes-divergent decisions of the federal courts of appeals, and opinion letters the Labor Department issues occasionally without public notice or input.

Our proposal seeks public comment and, once finalized, will state the Labor Department’s view clearly for all to consult. As the sole authority short of the Supreme Court with responsibility for how this law is applied coast-to-coast, we thought it past time to codify a simple, clear approach that can be applied consistently nationwide.

WHY THE GIG ECONOMY IS POPULAR: AMERICANS LOVE A SIDE HUSTLE

Our proposal is important, too, because of the increased attention in recent years to independent contractors.

The growth of the “gig” economy, in which cellphone apps provide a “platform” for connecting willing workers with interested customers, has provided new convenience and work opportunities for millions of Americans. But that economy and other developments are seen as subversive by those who believe that for most workers, being a company’s employee—not an independent contractor—is the only proper aspiration.

That’s the view behind a law California passed last year—AB-5—which requires companies to treat as employees a broad range of workers who previously would have been recognized as independent contractors. In response, some businesses stopped hiring Californians; Uber and Lyft announced they were suspending operations in the state, before a court-ordered stay gave them a reprieve from the law while they pursue appeals.

As originally enacted AB-5 was so unworkable that the state Legislature felt compelled to riddle it with amendments, establishing dozens of job-specific exemptions.

US EMPLOYERS HIRE 1.4M IN AUGUST AS UNEMPLOYMENT RATE FALLS SHARPLY

Unlike AB-5, our rule doesn’t propose radical changes in who’s classified as an employee or independent contractor. Instead, our rule aims to simplify, clarify and harmonize principles the federal courts have espoused for decades when determining what workers are “employees” covered by the minimum wage and overtime pay requirements of the FLSA.

Make no mistake, harmonization is needed. Right now, when determining whether a worker’s an independent contractor, some courts routinely consider the “importance” of the work she does to the company that hired her; other courts do not. And while courts agree that “investment” should be part of the analysis, some courts ask whether the worker will profit from the investment she makes in her work, whereas others (oddly) compare the dollar value of her investment to the total capital investment by the company. In two separate cases, a single federal appellate court reached different conclusions on the question of whether cable-slicers working for BellSouth contractors were employees or independent contractors.

WHAT THE 2019 CENSUS INCOME, POVERTY NUMBERS TELL US ABOUT BIDEN VS. TRUMP AND 2021

Our proposed rule aims to clear away the cobwebs and inconsistencies that have grown up around this analysis since the Supreme Court’s decisions more than half a century ago. To determine a worker’s classification, we ask whether he is economically dependent for work on the putative employer, or instead whether he’s in business for himself. To probe that difference, our proposed test focuses primarily on a worker’s control over his work, and his opportunity for profit or loss resulting from his own initiative or investment.

Once finalized, this rule will guide businesses, workers, the courts and our own Wage and Hour Division as we enforce the FLSA. We also hope the test will help states and policy-makers consider worker classification outside the FLSA context.

GET FOX BUSINESS ON THE GO BY CLICKING HERE

And unlike AB-5, our rule doesn’t aim to slant the analysis toward classifying independent contractors as employees. In part, that’s because we recognize there are powerful reasons why some workers prefer to be independent, rather than accountable to a company as its employee.

Being in business for oneself draws on two of America’s most deeply rooted traditions: freedom and entrepreneurialism. True independent contractors are their own boss. That appeals to countless Americans—the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that 79% of independent contractors “overwhelmingly prefer their work arrangement to traditional jobs.”

As Labor secretary, I’m struck how often young people tell me they want to start their own business; I’ve yet to meet one who says, “I dream of being an FLSA-covered employee.” Freedom from the strictures of a nine-to-five can be especially welcome to parents, caregivers and others who need greater control over their schedule and workload.

Of course, there are also benefits that come with being an employee covered by the FLSA and its minimum wage and overtime requirements. Some companies improperly claim their employees are independent contractors, to dodge responsibilities they owe under the law. Our Department will continue to bring enforcement actions against those businesses.

Our rule, once finalized, will hone our ability—and the public’s—to distinguish employees from independent contractors in business for themselves. Unlike AB-5, though, our rule will respect the independence—the freedom and entrepreneurial opportunity—that come with being your own boss.

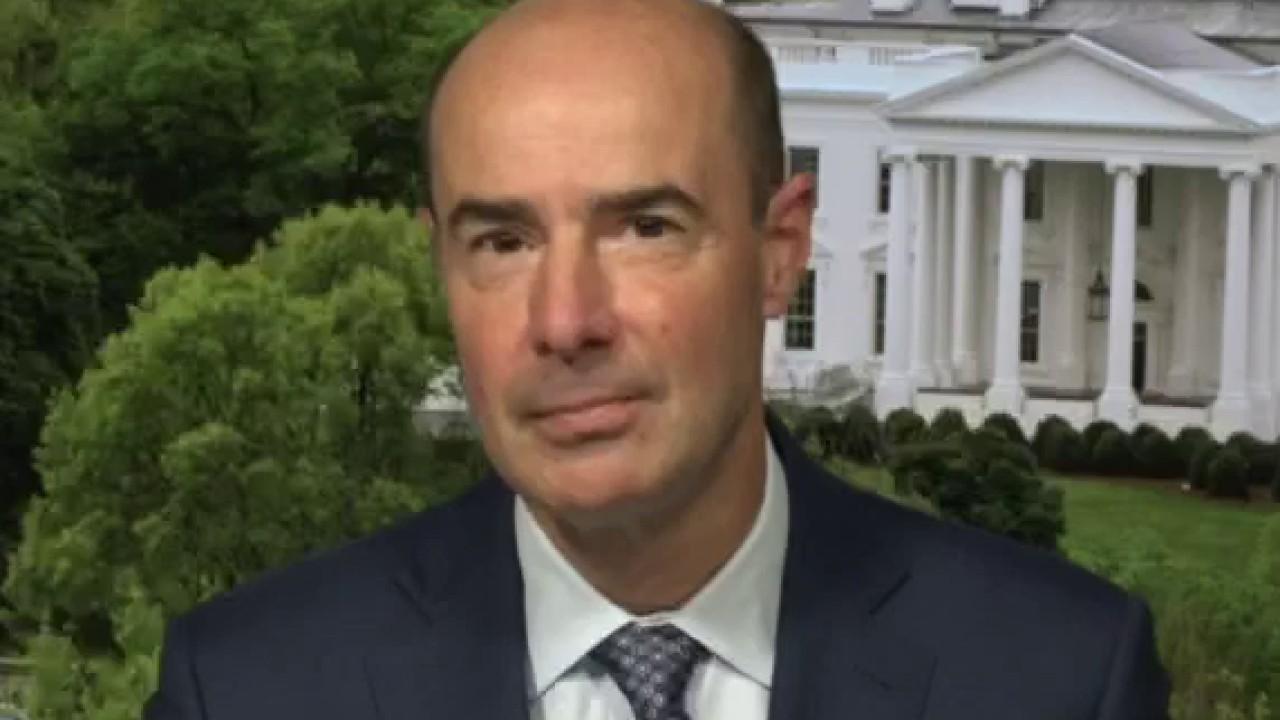

Eugene Scalia is Secretary of the U.S. Department of Labor.