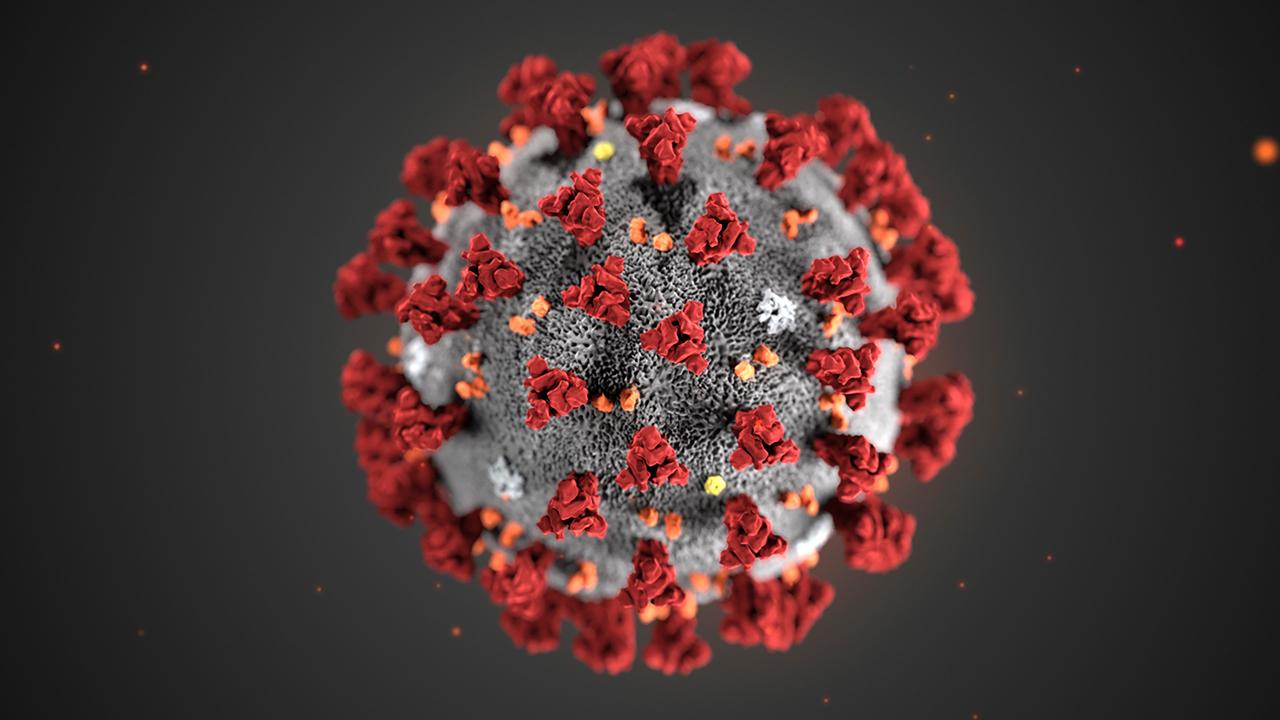

Coronavirus crisis – Hospitals need to do these 4 things now to prepare for a pandemic

The coronavirus epidemic is likely past the point of containment

We are now two months into the novel coronavirus outbreak with over 82,000 cases reported in over 47 countries. With no end in sight, this epidemic is likely past the point of containment.

The efficacy of the U.S. strategy to try to slow the progression of this viral respiratory disease through travel bans and quarantine efforts is questionable and only time will tell if it’s effective.

CORONAVIRUS VACCINE DEVELOPMENT COULD COST $1B

As public health agencies work to identify cases and implement control measures, the role of hospitals and health care becomes increasingly vital.

A new study reviewing the clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019-nCoV found that 26 percent required admission to an intensive care unit and 41 percent of cases were likely due to health care exposure.

In an already severe influenza season, what we do know is that health care systems around the nation must brace for a potential pandemic event.

This scenario means hospitals should start by dusting off those pandemic and surge plans. While most might think that health care preparedness involves making sure there are enough masks, ventilators, staff, and beds, there is a much deeper level of coordination and collective response that must happen to ensure readiness for an infectious disease event.

CORONAVIRUS WORKERS LACKED ADEQUATE EQUIPMENT, TRAINING: FEDERAL WHISTLEBLOWER

Health care facilities can act as amplifiers for disease during outbreaks, which makes their preparedness and infection prevention measures that much more vital.

The outbreaks of MERS-CoV in South Korea and SARS-CoV in Toronto were lessons in health care disease transmission and how quarantine efforts often fail, but effective health care response and infection prevention can stop the spread of the disease.

Looking at the long-term effects of a pandemic, health care systems can begin preparing by diving into the four “S’s” commonly used in emergency management: staffing, stuff, space, and system.

Evaluating these needs is the first step within the preparedness process but during this evaluation, the systemic issues within health care readiness and the vulnerabilities within our national approach to bio preparedness become apparent.

The number one asset to ensure a functional health care system is health care staff. Those frontline workers who actually provide the continuum of care to patients – physicians, nurses, cafeteria staff, housekeeping – are all essential personnel needed to keep a health care facility operational.

APPLE CEO TIM COOK: CHINA GETTING CORONAVIRUS UNDER CONTROL

Yet, during a pandemic staffing is one of the hardest hit “S’s.” To plan ahead, health care facilities need to begin looking into temporary staffing options, volunteer health care organizations and potentially contacting retired employees for assistance.

Beyond the staffing volumes, having those employees trained and skilled in infection prevention measures is necessary to prevent health care transmission of the disease.

Maintaining this level of skill can be challenging though, as the turnover rate for nurses in the United States ranges from 8.8 to 37 percent depending on the geographical location.

Moreover, the volume of infectious disease physicians is on the decline and infection prevention and control programs are consistently understaffed.

In terms of the “staff” portion of health care preparedness, it’s not merely enough to have the volume of people, but to also ensure they have the skills to be safe.

Next, the “stuff” in this preparedness matrix, which includes vital supplies needed for patient care. These include personal protective equipment (PPE), pharmaceutical products, and other equipment.

Supplies are always one of the first “S’s” to be impacted before a pandemic even starts. Often this is due to hoarding but supply of these materials has become a greater issue during the 2019-nCoV outbreak.

Previously, we’ve seen hoarding practices in the 2009 H1N1 pandemic and the 2014 ebola epidemic where health care systems began ordering more supplies than needed, creating a significant burden on the supply chain.

Unfortunately, in this current outbreak, the supply of PPE has become increasingly strained as a majority of the masks and other vital supplies are manufactured in China.

In fact, the World Health Organization has recently addressed this raising demand for PPE and that “global stocks are insufficient to meet the needs of WHO and its partners.”

To address this issue at a local level health care facilities need to begin communication and coordination strategies with manufacturers and public health agencies to access local and state supply caches and conservation strategies.

As PPE supplies become increasingly strained, there also needs to be plans to re-use certain PPE based off guidance from the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Beyond the scope of PPE though, should widespread transmission of 2019-nCoV occur in the United States, insight into the clinical characteristics of those patients requiring hospitalization suggests that intensive care units will likely be heavily utilized, as will antiviral and antibacterial therapies, noninvasive ventilation, etc.

Real estate, or “space,” is a third asset we don’t often have the luxury of expanding in a health care facility.

It may seem superfluous, but even in non-emergent times, hospital space is often highly sought after for storage and work areas alike.

Health care is only growing in the United States but are two options to remedy this shortage during a biological event or surge.

First, expand within the brick and mortar of a facility by turning units, cafeterias, waiting rooms, and any unused space into something that can be used for clinical purposes.

Second, establish alternate care sites. This can include mobile satellite vehicles, tents, and other forms of space that can be used for patient care. However, a key issue when it comes to expanding a facility’s footprint is the staffing, both in terms of those working in them but also the security of the satellite area.

Lastly, the fourth “S” is system. To keep all units, floors, departments and facilities operational, health care must function as a system.

Leadership is key and buy-in from all levels of administration will greatly affect how well, or how poorly, a facility will do during a pandemic event.

Effective and collaborative leadership is critical and those who are willing to utilize their subject matter experts are better poised for success.

The time to prepare a health care system is now, not during the actual response to a pandemic.

While we can underscore the importance of this strategy, there are systemic roadblocks within U.S. health care that challenge biopreparedness efforts.

The United States saw bolstered health care readiness following the 2014 Dallas Ebola cluster, but engagement has dwindled.

A 2017 Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General (GAO) report found that while hospital administrators disclose better readiness for diseases like ebola, they struggled to maintain preparedness due to competing priorities and the “need to focus on more common hazards, such as natural disasters.”

Funding for the tiered hospital system established in 2015 to ensure American health care readiness for special pathogens, like ebola, is set to expire which would leave only 10 regional treatment centers in the U.S.

The collapse of this tiered approach also sets a tone of disengagement for U.S. health care bio preparedness which does little to encourage hospital leadership to invest in more costly preparedness for events they admittedly view as unlikely.

GET FOX BUSINESS ON THE GO BY CLICKING HERE

Even those infection prevention programs that were primarily responsible for ebola preparedness have cited competing interests by hospital administrators that focus on those healthcare-associated infections tied to mandated reporting rather than preparing a hospital for potential outbreaks. Unfortunately, this does not change the fact that outbreaks, epidemics, and even pandemics, will happen and we will need to be prepared.

The end goal for a health care system is to create a “safe system of work” which includes administrative controls, engineering controls, proper work practices, infection control procedures, environmental hygiene, and appropriate use of personal protective equipment.

From a patient’s hospital admission to discharge, every step is an opportunity to apply this framework of safe systems and prevent infections from spreading.

This all starts with the i3 approach – identify, isolate, and inform. This strategy means rapidly identifying patients through triage, isolation of suspected infectious patients, applying infection control measures to prevent exposures, and making the appropriate notifications internally as well as externally (i.e. public health authorities) to inform and ascertain risk.

To accomplish the i3 strategy, frontline staff must be trained in properly donning and doffing PPE and must be capable of implementing infection control measures.

To effectively and efficiently do so, hospitals must have the staff, supplies, space, and strategy.

This may sound like a small feat but it is a huge undertaking in reality. Ensuring each frontline staff has the tools, resources, and training takes money, time, and effort.

The ongoing 2019-nCoV outbreak is our opportunity to apply these lessons and strengthen the critical infrastructure that is health care in the United States.

Syra Madad, D.,H.Sc., M.S.c, MCP, is the Senior Director for the System-wide Special Pathogens Program for New York City Health + Hospitals. Saskia Popescu, PhD, MPH, MA, CIC is a Senior Infection Prevention Epidemiologist for HonorHealth.