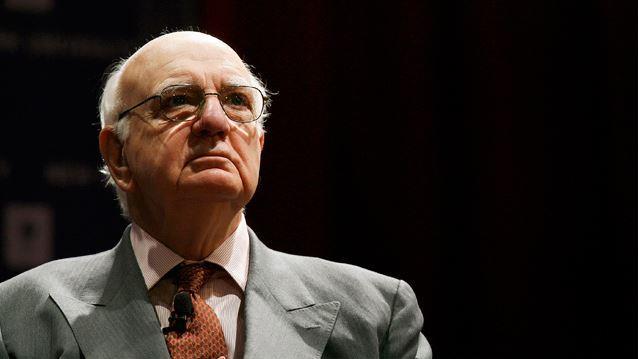

Geoff Shepard: Remembering Paul Volcker, former Fed chairman – A man I was privileged to work for

Paul Volcker was an intellectual giant, and I had a front row seat to understanding his genius while working with and for him early in his career.

Paul Volcker, the legendary Federal Reserve Chairman who tamed rampant inflation in the 1970s, died one week ago at age 92. He was an intellectual giant, and I had a front-row seat to understanding his genius while working with and for him early in his career.

I’d been awarded a White House Fellowship in 1969, and Treasury was my first choice for the year’s work assignment.

I’d taken every business and tax course offered at Harvard’s law school, but the Tax Reform Act of 1969 had passed just before my arrival, removing those issues from Treasury’s table.

PAUL VOLCKER, EX-FED PRESIDENT, DEAD AT 92

Paul was undersecretary for international monetary affairs – third most senior in the Department and had just turned age 42.

He’d first joined the Federal Reserve staff in 1953 and had served as deputy undersecretary for monetary affairs in the Johnson administration. He was a Democrat, but such a monetary affairs expert that Nixon wanted him, too.

In those days, it was said that Treasury was run by bankers for the benefit of banks – rendering a newly minted lawyer somewhat superfluous. Still, it was a golden opportunity to learn.

For four months, I sat outside Paul’s office, literally between him and the three secretaries he kept busy all day and late into many evenings. I saw every document coming in or out of his office – and joined every meeting.

Those meetings ran non-stop. We were already experiencing the financial strains that culminated in Nixon’s 1971 decision to close the gold window, which triggered the collapse of the Bretton Woods system that had coordinated world financial markets since World War II.

As undersecretary, Paul was also a director of OPIC and Fannie Mae. He was a singularly influential voice throughout those turbulent financial times.

My memories, however, are far more personal. I asked him once just when he had time to think – since, from the moment he arrived each morning, all kinds of people trooped into his office, seeking advice and counsel.

He said you had to have thought things through before assuming office, that at his level there was no opportunity for on-the-job training.

You were called upon to react, not to contemplate – that could only come after leaving office. It was an early rendition of Kenny Rogers' "There’ll be time enough for counting, when the dealing's done."

At 6' 7", Volcker was exceptionally tall but stooped. He constantly smoked small plastic-tipped cigars called Tiparillos.

He spoke softly and tended to mumble, so people hung on every word. I’m not sure if this was intentional; perhaps his mind was moving much faster than his tongue.

At 6' 6", I was an inch shorter than Paul, but we appeared to be the same height. I would tell my friends that, "Paul and I see eye-to-eye on economic affairs!" It was my favorite inside joke.

"America would be better off, if we had leaders who followed the Volcker example of service in the cause of country over party."

One challenging thing about trying to follow Volcker’s office discussions was their frame of reference.

The usual issue was how other country’s central banks would react to some U.S. initiative. If we do this, how will England or Germany respond?

Yet, participants never called the bank by name (Bank of England or Deutsche Bundesbank) or even used the respective central banker’s title (Chancellor of the Exchequer).

No, they used the last name of its current head, as in “How will Volcker react?” It was as though a given central banker’s personality was key to predicting a particular reaction.

As a newly arrived neophyte, I’d try to follow the conversation but never was sure which countries were being discussed.

FED'S POWELL FINAL PRESS EVENT OF 2019: RECAP

When our Fellows class was invited to a very formal White House event, I realized that I didn't own a white tie and tails, and that it would be difficult to find a rental in my size.

I worked up the nerve to ask Paul if I might borrow his. He sheepishly confided that he didn’t own one, either – but quickly wrote out the name of his rental store.

On my way out, he said, “Be sure to tell them that I sent you – and said you are to get the one usually saved for me. Otherwise, they’ll give you some cheap knock-off designed for a waiter.”

Few others in this world can claim to have worn the same clothes as the legendary Paul Volcker!

Of course, Volcker’s rise to national prominence came from when he was appointed to head the Federal Reserve Bank, first by Carter and then re-appointed by Reagan.

It was then that he so restricted the money supply that interest rates were driven to historic highs – but the battle against runaway inflation was won.

In the midst of this turmoil, I was part of a prestigious group granted an audience with Paul at the Fed.

Now older and wiser in Washington’s ways, I told his secretary that I’d worked for him as a Fellow and asked to pay my respects before our scheduled meeting.

She agreed that I might drop by a few minutes in advance. As usual, Paul was running slightly behind, so we only chatted briefly, while walking down the hall to the large conference room.

Substance aside, what impressed other group members was that I actually walked into the meeting with the chairman himself!

I still didn’t know much about monetary affairs but I’d learned how to play the Washington game.

GET FOX BUSINESS ON THE GO BY CLICKING HERE

I last saw Paul in 2008, at an 80th birthday party hosted by the Economic Club of New York.

At the VIP reception beforehand, we exchanged pleasantries. I didn’t expect him to remember me, but he did recall that Treasury had had a hard time finding substantive work for its assigned Fellows.

I fully agreed, but pointed out that I had learned a huge amount, from Treasury and from the Fellows’ year-long education program, such that I knew quite a bit by the time I joined the White House Domestic Council after my Fellowship year. I credited him for much of that learning.

This was also the same event where Paul announced his support for Barack Obama, saying it was time for oldsters to step aside and allow a younger generation to assume leadership responsibilities.

Paul then became the “grand old man” of Obama’s responses to the Great Recession, chairing his Economic Recovery Advisory Board.

I confess I fear he was more of a figurehead than the man in charge, as perhaps he should have been.

Paul was a key public servant, who served in or advised every administration from Dwight Eisenhower to Barack Obama.

I’ve spent the past year as alumni president of the Fellows program. It surprises incoming classes when I say that there once was an era where experience and expertise in complex areas were far more important than party designation and that it was not uncommon for members of one party to serve with distinction in senior positions under a president from the other.

America would be better off if we had leaders who followed the Volcker example of service in the cause of country over party. But, for those that try today, it may be all-but-impossible to match Paul’s generational intellect.

Following his Fellowship year, Geoff Shepard served for five years on the Domestic Council, including acting as deputy counsel on Nixon’s Watergate defense team. For more visit www.geoffshepard.com