How Russia's invasion of Ukraine will result in greater chip shortage

The Ukraine war effect on chip manufacturing may not hit for another 3 to 6 months

Energy exec blasts Rep. Khanna for 'irony' on oil stance

American Petroleum Institute CEO Mike Sommers argues Democratic politicians are continuing to 'browbeat' U.S. oil companies.

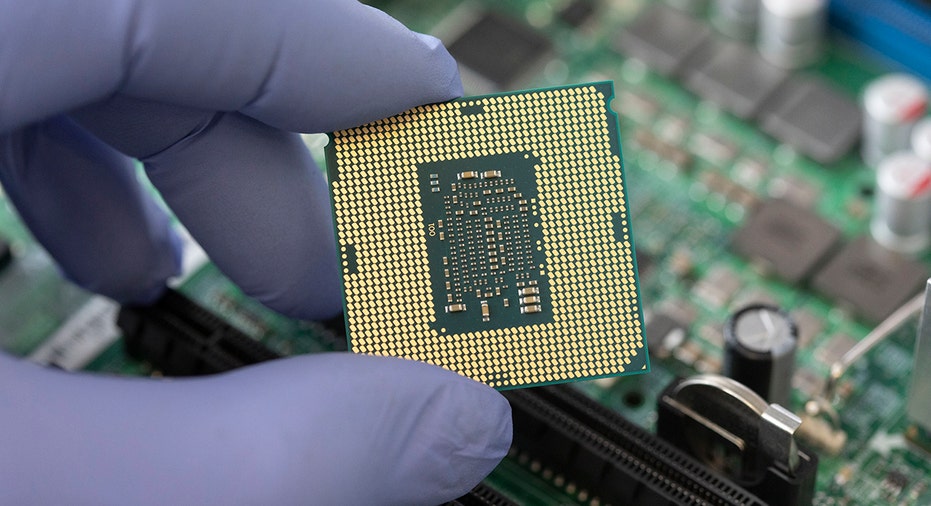

The war in Ukraine has threatened to worsen an already concerning shortage in semiconductor chips.

"Three of the major companies in the world [for neon] are based between Mariupol, which has been ravaged by the war, and there’s two, I believe, in Odesa," Dusin Carmack, research fellow for cybersecurity, intelligence and emerging technologies at the Heritage Foundation, told FOX Business. "It’s going to be maybe three to six months before you see major impact … but if this is an extended war, this is going to cause supply chain issues."

RUSSIA INVADES UKRAINE: LIVE UPDATES

The U.S. has suffered a semiconductor shortage that has contributed to supply chain disruptions and further ripples across the economy. U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo reported in February that some companies' supply fell from a month’s worth to just a few days’ worth, and last week the White House warned of "escalating vulnerabilities" to the U.S. due to the shortage.

The U.S. Senate on Monday again approved a bill to provide $52 billion in U.S. subsidies for semiconductor chips manufacturing in a bid to reach a compromise after months of discussions. | Getty Images

The war in Ukraine will only further strain that situation, Carmack noted. Companies may keep between three and six months of supplies in case of a shortage, but they have already started eating into those reserves.

"In the near-term, I think smaller semiconductor fabs, or those who didn’t have the capability to diversify their stock, can see some immediate impact, especially if they relied on [Ukraine] for their supplies," Carmack said, highlighting that some companies moved to diversify after the 2014 invasion of Crimea.

CONSUMER PRICE INDEX, INFLATION EXPECTATIONS, BANK EARNINGS TOP WEEK AHEAD

Some reports indicate Ukraine provides up to 90% of neon gas supplies that the U.S. needs to operate lasers necessary to manufacture the chips, but more concerning is Russia’s role as a bulk supplier for rare earth metals like palladium.

Russia provides roughly 28% of the world’s palladium supply, and 7% of the U.S. supply, according to historic data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC).

| Ticker | Security | Last | Change | Change % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMRK | NO DATA AVAILABLE | - | - | - |

| ELA | ENVELA CORPORATION | 12.98 | -0.09 | -0.69% |

| XPL | SOLITARIO RESOURCES CORP | 0.74 | +0.02 | +2.86% |

| SPPP | SPROTT PHYSICAL PLATINUM & PALLADIUM TRUST | 17.00 | -0.08 | -0.47% |

"You’ll notice that the U.S. hasn’t blocked, per se, palladium exports from Russia," Carmack said. "I do know that a London exchange said they’re going to block any new imports of palladium from some of Russia’s biggest suppliers."

"That doesn’t mean those resources can’t connect properly with manufacturers, but it does signal that broader exchanges in terms of huge markets are going to be impacted," he added, noting that palladium prices recently jumped – in fact hitting a year-long high of $3,302 per ounce on Mar. 8, according to Monex.

CLOCK TICKS TOWARD RUSSIA DEFAULT AFTER S&P DOWNGRADE

Palladium shortages will also impact other manufacturing capabilities, such as catalytic converters. Car manufacturers started collaborating in early 2022 to identify ways to innovate on future chips, but one of the significant ways they can avoid similar issues in the future is to diversify their sources of necessary materials – a process that may prove difficult since China remains the predominant provider for rare earth metals.

Carmack pointed to Africa – primarily South Africa – as well as parts of South America as most promising for future mining: South Africa already exports around 17% of the global supply of palladium, making it the second-largest exporter in the world.

The U.S. could consider how to increase its on-shoring of mining and refining these metals, or risk leaving itself and its allies reliant on China for its rare earth metal supplies.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE ON FOX BUSINESS

"I think we’re always advocating to remove the red tape preventing our capabilities," Carmarck explained. "We essentially blocked a lot of production capabilities in the United States."

"It’s one thing we have to consider as we go forward – not trying to fight these geopolitical battles with one arm tied behind our backs," he added. "If you are a geopolitical observer and you see this U.S. and China relationship becoming more frayed, I think you would want to diversify your imports as much as you could."