Are chat rooms safe for children and teens?

Danger tends to appear when a user sends an external link to another website or video chat

Chat rooms can be scary for kids and lead to potentially dangerous situations, but experts say they are not as threatening as information-sharing social media platforms.

Chat rooms are online platforms that offer strangers a place to talk in group “rooms,” similar to a text group chat but most users are anonymous.

The anonymous feature is what can be scary for kids because it hides the identity of the other users they are speaking to; at the same time, the anonymous feature is necessary for kids to stay private.

Students sharing a laptop (iStock)

“You can pretend who you are,” James Achilles, vice president of children-oriented chat and game website Kidzworld.com, said of other chat room websites that claim to be geared toward teens and children. He said activity on Kidzworld has surged since the coronavirus pandemic forced kids to stay home from school.

“We work so aggressively on moderation, safety and privacy,” he said of his site but added that on other platforms, “bad actors have easy access.”

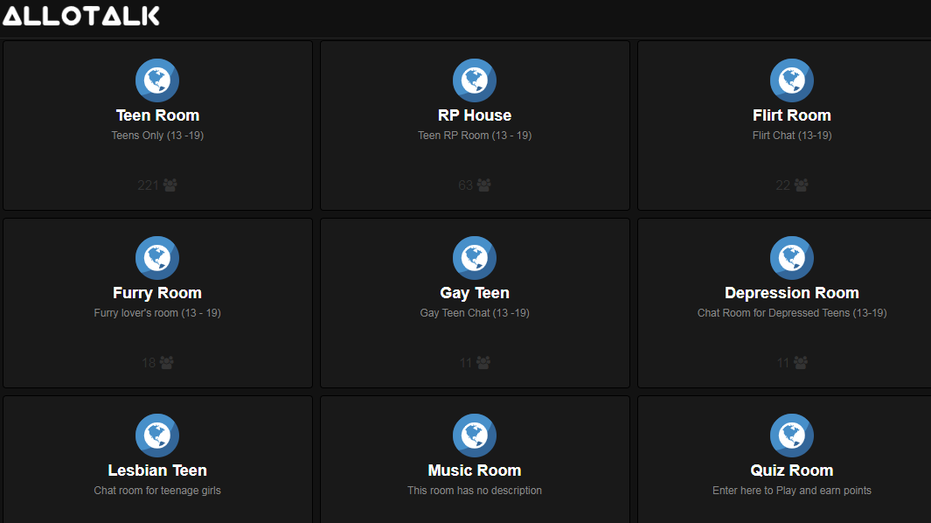

Many chat room websites offer themed rooms; some of these themes range from interests to specific sexual preference; for example, on Allotalk.com, users between the ages of 13 and 19 can choose to talk on the general “Teen Room,” the “Gay Room,” the “Depression Room” and even the “Furry Room.”

AlloTalk.com teen chat rooms

Some chat rooms geared toward “teens” and “kids” can be easily accessed by adult predators who may pose as kids and try to groom them into having inappropriate conversations. AlloTalk directed FOX Business to its rules when asked how the website protects teens on the site.

Most of the first Google website suggestions that appear when users search "teen chat room" do not require any kind of authentication for users to join, or they require users to click a box indicating that they are entering a chat room designated for teenagers or children that older users can easily bypass.

FACEBOOK MESSENGER FOR KIDS TO LAUNCH IN 70 COUNTRIES

Most chat room websites also offer private chat features that allow users to have one-on-one conversations. When users appear online, they may receive unsolicited private messages from other users inviting them to chat on Zoom, Skype or Google Hangouts instead.

These private invitations are where things can get dangerous, Achilles said.

Kidzworld.com, which centers its business model on the Children's Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), uses algorithms and human moderators to make sure children are not signing up with their real names or having what appear to be inappropriate conversations and ultimately stay safe on the platform.

Kristen Cohen, assistant director of the Federal Trade Commission’s Division of Privacy and Identity Protection, said websites like Kidzworld.com that are geared specifically toward children under 13 must comply with COPPA rules. That said, children are not protected by COPPA on chat rooms that may be geared toward "teens" in general.

Kidzworld website (FOX Business)

Kidzworld has a scoring system so that if a user says something inappropriate that gets picked up by the website’s algorithmic system, they get a warning; the next time they say something inappropriate, they get a penalty that prevents them from talking to other users for a certain amount of time; and if penalties continue, users can ultimately get fully muted.

If a user appears to have a pattern of penalties, the website’s human moderators can step in and look at individual messages.

“People who send links to Zoom, Google Hangouts and other video chats are where you don’t want kids going,” Achilles said. “These are flagged on a high level. Our moderators are catching bad actors almost immediately.”

ARE KIDS SPENDING TOO MUCH TIME ONLINE?

And even though bad actors do exist, most children are not being groomed and exploited online, said David Finkelhor, director of the UNH Crimes Against Children Research Center.

“Things we do know: The majority of majority child sexual abuse and exploitation occurs in offline venues -- at home, in their neighborhoods, in other people’s homes,” Finkelhor said. “The internet is a place where children can be recruited, but there is no evidence that it is an unusually dangerous place.”

The majority of exploiters who target children online do so on platforms that aren’t anonymous, he said, because the goal is to earn trust and eventually meet the children in person. They may target children on more familiar platforms like Facebook Messenger, Instagram or simply via text message.

Most groomers “exploit children by preying on their need for friendship, interest in romance, finding out about sex and romance, preying on the fact that kids aren’t sure about their sexual orientation,” he said, which is why young boys are particularly vulnerable to online exploitation.

A person working on a laptop in North Andover, Mass. (AP Photo/Elise Amendola, File)

John Shehan, vice president of the Exploited Children’s Division at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, similarly said one strategy groomers use is to get information about a child's "interests, friends, family and other personal information" on social media.

"This information can then be used to establish contact and build rapport with a child victim by pretending to share the same interests, known mutual acquaintances, or pretending to be the same age range of a child or a member of the opposite sex," Shehan said.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE ON FOX BUSINESS

He added that "once sexually abusive images/videos have been exchanged, knowingly or sometimes unknowingly ... bad actors can escalate to blackmailing/sextorting the child for additional, and often more egregious, content. The most frequently seen blackmail tactic involves a bad actor threatening to disseminate existing images/videos of a child victim to the child’s parents or friends."

Finkelhor brought up the fact that some kids “are interested” in talking to groomers despite knowing they are not the same age but do not realize “these people really don’t care about them and are only interested in exploiting them.”

Blocking chat rooms or preventing kids from using chat rooms will likely only provoke children to find ways to get around those rules and feel discouraged to talk to their parents or guardians about the inappropriate things they see online.

“What’s likely to work is having conversations and talk about why [certain conversations and actions] are inappropriate, even if kids say they’d never do that, it’s important for parents to talk about what kinds of things people might do," Finkelhor said, adding that parents can mention that they are giving advice so their kids can “help their friends, too.”